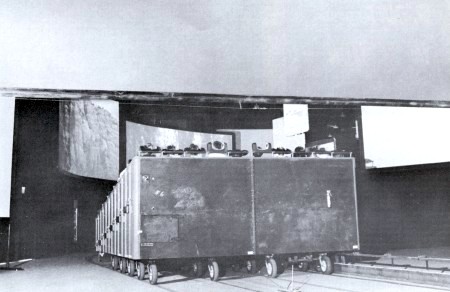

"The American Journey"

Source: (both

photos) Elevator World Magazine, Vol. XII, No. 9, September

1964

One of 12 "Moving

Grandstands" seating 55 people begins its travel along "The

American Journey," the multi-screen film presentation at

the Federal Pavilion. Note the adjustable headsets for audio mounted

on the backs of the seats.

|

|

|

In the Federal Pavilion, viewers

are conducted on a trip through American history in what might

be called a drive-along theater.

Designed, built, installed and

operated by Cinerama, the exhibit features bus-sized open vehicles

which transport visitors around a city bock-square expanse of

motion pictures, still photography and three-dimensional effects.

Screens move aside, go up and down, even form a tunnel for the

buses to drive through.

The 12 moving grandstands each

seat 55 persons. A new group of 55 begins the trip every 80 seconds.

Each vehicle is fitted with individual earphone equipment for

the presentation's soundtrack.

Measuring 18 feet long and 16

feet wide and containing rows of seats each set higher than the

last, the vehicles glide along a 1,250-foot track circling the

pavilion building at a rate of about one mile per hour.

Jeremy H. Lepard, in charge of

the film project described the film exhibit which Cinerama has

created a the Federal Pavilion for the U.S. Government. "Audiences

actually have to learn a new way of looking at life-through-movies.

It is something like walking down a strange street. Our technique

produces the real feel or aura of an era."

Viewers are whisked through an

environment something like a big, twisting tunnel, only this

environment is mostly comprised of some 120 screens of various

sizes and shapes. As Lepard describes it, "We've picked

little nubs, shots, from other times to create an overall feeling

of the American historical heritage. I expect that many people

will return time and again to get the full information of our

show."

Some 2,000 viewers an hour, 20,000

a day, can be accommodated at the Federal pavilion film show,

which is under the supervision of U.S. Commissioner N.K. Winston

and the U.S. Department of Commerce. One of the vehicles has

seats equipped with a five-channel selector speaker system, so

a viewer can elect to hear the narration in either French, German,

Spanish, Italian or English.

The narration was written by

noted science-fiction author Ray Bradbury and is delivered by

John McIntyre of "Wagon Train" TV fame. Over 170 movie

and slide projectors are utilized to create the environmental

effect of the 13 1/2-minute ride.

"The American Journey,"

as the show is entitled, begins with the viewer being surrounded

by the mysterious ocean, filled with unnamed sea monsters, which

our ancestors knew on their way to America. It is followed by

depictions of the Indians to be found here, then shots of pioneers,

native animals, early inventions, historical events, the trek

Westward and the scenic wonders of America. We are brought up-to-date

with some startling rocket effects, provided courtesy of NASA

and the U.S. Air Force.

Over 100 historical societies

provided material for the show, as well as the Library of Congress,

the National Archives and the Smithsonian Institute. Cinerama

sent camera crews out to many sections of the United States to

film various American landscapes.

All this is on the second level

of the Federal Pavilion. On the first level, photos along with

other graphics depict events in the American past and controversies

in the present which have been or are topics of discussion and

interest.

The Federal Pavilion also houses

a more-or-less conventional 600-seat theater and a 200-seat auditorium,

both of which are used for the presentation of films. A significant

one is a U.S. Navy cinematic duplication of a submarine's trip

under the Arctic ice, a missile firing on the submarine Nautilus

and a ride with the Blue Angels flying team.

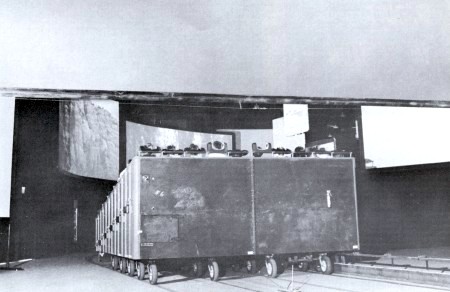

Source: Industrial Photography,

Vol. 13, No. 5, May 1964

|

A rear view of one of

the "Moving Grandstands" as it makes its way through

a tunnel of movie screens. Note the rail to the right of the grandstand

which provides a contact point for power and audio and guides

the grandstand along its route.

|

|

-

The Script

-

"The American Journey"

-

by: Ray Bradbury

|

Here lies our past. Look

at it. Combine your fabled history with the challenge of noon

today so as to move with heart and purpose toward a tomorrow

of your own choosing.

-

- A sea of water.

- A sea of grass.

- A sea of stars.

-

- A wilderness of ocean.

- A wilderness of land.

- A wilderness of sky.

- Remember these. These

were. These are. These will be your destiny.

-

- First, the wilderness

of the sea. In darkness you move upon it. "Don't go!"

the fearful cry, "The world is not round! You will fall

from the earth! Fierce dragons lie before you!"

-

- Here in the brief hour

before the continental dawn, before you pathfind the wilderness

of grass, look deep at this wilderness of water. Here be menaces

of fish to feed your future colonies. Here giant whales. Those

flourishes of God, whose wisdom rendered down to oil will light

your lamps.

-

- Now ten thousand ships

whelm in through island straits and stand off hearing a single

sound from the New World. Listen. The landfall of morning. The

crash of real surf on real land runs old nightmares off.

-

- Now name yourself Columbus

and found Hispanola. Wade with Balboa along Pacific shores until,

with Vespucci, you print your first name, Americus, upon a wild

that should have been far Japan or elephant India. But signs

itself, at last, plain "America."

-

- Soon you stand small in

Virginia and Massachusetts and see the forests primeval. God's

bounty of trees. The murmuring pine and the hemlock as far as

eyes can see. Later, you might apologize but now you seize forth

hatchets, handsaws and axes, back-off and give a whack! And God's

wilderness falls down.

-

- To reveal the Indian Tribes,

as far again as the eye can see, the teepees of the Dakotas,

the pueblos of the Zuni, the sod huts of the Kansa -- the United

Indian Nations.

-

- With Indians before and

English close behind you prepare for raw excursions and revolts.

You send Ben Franklin forth to juggle lightening. And plug to

your roof one of old Ben's Lightening Rods in case God judges

your revolution amiss. You fire forges and hammer tools and weapons

along the colonial shores. Declare your independence. Fight your

revolution. Build a war. Build a Constitution and try to live

in it.

-

- Then set the restless

free to pathfind a raw territory to translate its French names

into Indian Oklahoma, Minnesota and the far Dakotas, with Lewis

and Clark in the lead.

-

- While the spunky nation

of half-grown boy mechanics and electrical experimenters blow

themselves up with steam devices; with Robert Fulton invent excavating

machines and "Fulton's Folly" which did not blow up.

And even then, with the sea wilderness and the wilderness of

land yet unconquered, you begin to dig and build an Er-i-e canal.

-

- You churn the Mississippi

up and down. Plant cotton. Invent a Cotton Gin. And thus, spin,

loom, cut and plant back the wilderness. Invent machine reapers

that harvest your grain and send your hunters forth to a terrible

blood harvest: fifty-million wild buffalo slaughtered.

-

- And seeing the wilderness

shot down before him, your John James Audubon goes forth to catch

its winged beauties with eye and hand and pen before they fly

south forever.

-

- The wheels roll off the

water onto land. As Herman Melville takes his ink and writing

pen to sea and with that pen harpoons him "Moby Dick, The

Great American Whale." And the whale is the wilderness put

down. The whale is God's sea and the mystery which must be conquered.

The whale is death which must be stayed.

-

- So the wilderness of ignorance

is cleared by science even as the frontier is pushed back. And

you stand at Independence, Missouri. The cry from Sutter's Mill

is "Gold!" And the wild climate of people spills toward

the landfall of California.

-

- And coming with it, the

"singing wire." The telegraph poles planted like strange

electric trees across the west. Bringing the news that not only

is America reaping the wilderness grain, but tossing forth win

rows of blue and gray. A harvest of brothers; the civil dead.

With mini-ball and cannon you suicide. You commit your life away

in the North and South.

-

- Now mend the war and weld

a peace. From here on down to the Cherokee Strip it's new steel

mills. The laying of the Atlantic Cable. The first elevated trains

skirt the cities.

-

- And far out on the prairies,

the Indians, dazed by the comings and goings of the wild White

Men, see a dragon monster late at night as the railroads meet

in wondrous collision at Promontory Point, Utah. Telephones ring

and electric lights shine through the gas-lit lamps!

-

- And with the far Pacific

shore reached, farmed and citified, American boy-man, great child

scout, freighted with gravity, riveted to an earth you have now

trampled to subservience, turn from the tides of the sea and

the tides of Buffalo Grass and look at fresh wallows of sky.

You hear the birds at morning, and strong with new blasphemy,

dare take wing. And at last those boys who jumped from haylofts

become two men at Kitty Hawk.

-

- And America rides, skips,

jumps, soars into the free wild air of the Twentieth Century.

And flies right into and out of another war. Balloons ascend

from the great three-ringed circus that is life in the good old

U.S.A.

-

- Meanwhile you've sent

an Admiral to find the North Pole. Dug a canal in Panama. Filled

the country with phonographs and movie theaters. You make movies

bigger and bigger and bigger! You send a Byrd to the South

Pole and appropriately enough he says "Jules Verne leads

me." And put one man in a lonely craft across the Atlantic

toward Paris and immortality. Set off a rocket and delivered

some first Rocket Mail. Fight a second World War and put fifty-thousand

planes over Europe. Split the atom.

-

- And find yourself now,

four-hundred years later, a nation of fifty states. Two hundred

million people who have nailed down the wilderness; who've cut

the long grass and breathed the warm winds of freedom. You are

the people who always want futures; for you don't like the way

things are.

-

- You didn't like the mountains

so your reared them up in skyscrapers. You didn't like time and

distance so you turned it inside out with jets. You didn't like

pain, disease and death so you put two hundred thousand hospitals

across that dark and dangerous territory.

-

- Now, at last America stands

lit upon the ancient wilds; one huge electric city facing the

future. You've been part of three motions of weather: A wind

of change that blew across oceans. A weather of need that strewed

wild flower human seed to populate the four corners of no where

and make it somewhere. And the boy-mechanics who flew the kites

and lit July 4th rockets who now, grown men, make ready for the

time of your future voyaging.

-

- Look far away from the

seas of earth, the seas of grass, and the lights in your constellation

cities, toward the lights in the sky. The weather of change is

eternal. The warm American climate carries its momentum up.

-

- Alert, you shape a vast

unsleeping seashell ear, which hears tomorrow rolling in across

the shoals of time. From Cape Kennedy to California you mix the

elements of raw mythology. From chemistries of earth, fused with

air, you strike forth fire. But what goes up must often come

down. But, as never failed; can never succeed. We will fall but

to rise again.

-

- To send Telstar, which

speaks in tongues, across lake ponds that once were ocean seas.

And fly Tiros to tell the weather of man's earth and lift the

sons of Herman Melville and Jules Verne to guess the weather

of America's soul.

-

- But why? Why fly out to

the stars with so much yet undone on earth? The answers lie in

what we do not know: What is the sun? How does it send

its searchlight waves of heat through frigid vacuum paths of

blackness? What lies beneath the mountain range and plain of

moon crust that beams down on us nightly? Is man the only thinking

life within the endless curve of universal space?

-

- The cures you find in

rocket flight will cure your maladies at home. The weightlessness

you give yourself in rockets will lift the weight of sick disease

from earthbound people. You go to find. To know. To learn. To

build. And move on yet again. Man seeking peace may find it at

last in a mutual attack. A last great war. Not against himself

but against the hard challenge of space.

-

- So, light brother and

dark, in a nation and of nation upon nation in the world, give

legs-up to each other. Build pyramids of men and fire toward

landfalls on the moon and bright new Independence Days. Looking

back from space see your birthplace earth. The old wilderness

dwindle as the human race reaches for eternity, survival and

immortality in the next billion years.

-

- Man, God made manifest,

goes in search of himself. The great outpour of all nations which

crush the Buffalo Grass and reach the end of one frontier, now

finds greater challenges in the star wilderness above.

|

-

The Script

-

"Voyage to America"

- These are Americans, more

than a hundred-ninety million of them. A people whose story is

one of movement and change. A record of migration that is unique

in history.

The Pilgrims came to Massachusetts

to practice freedom of worship. Others from England, from the

Netherlands, from France and from Spain, founded settlements

of their own, hoping to find in the New World opportunities which

the Old World had denied them.

The journey was hard. One

out of three died on the way. Of those who survived, more than

half entered their new country under some form of servitude.

Up to seven years of forced labor in exchange for their ocean

passage. There were others whose servitude had no end.

Year after year they came.

The slave and the free. Educated and ignorant. Radical and conservative.

Some with money and some from debtors prisons. All rich with

memories. All eager to build anew.

Political independence

was the first step. They still had to cross the wide continent

to people the empty land and make it their own.

In Europe, as the people

grew desperate under the pressures of social and industrial revolution,

there seemed to be only one refuge: the New World. Within a hundred

years more than forty million human beings crossed the seas to

America. They came in waves. First the Irish; four and a quarter

million in all. They built our first chain of canals. Railroads.

The cities of the Middle West. Between 1830 and 1840, the population

of Illinois trebled and Chicago multiplied eight times as westward

moving Americans joined the new wave of immigrants from the Old

World.

From Western Europe came

the English, Scottish and Welsh. Scandinavians. Germans. Austrians

and Swiss. Fifteen million of them. Bringing with them their

skills, their education and their ways of life. They helped to

create something never seen before: an open society so fluent

and so dynamic that those who arrived entered at a status equal

to those who were already there.

In the thirty years following

the Civil War, over a hundred-thousand miles of railroad track

were laid, mostly by immigrants. Now the land was open from coast

to coast, ready to receive the millions already on their way.

Men and women of many races and creeds. Protestant, Catholics

and Jews.

From Southern Europe came

the Italians: six million. From Central and Eastern Europe: the

Poles, Rumanians, Lithuanians, Hungarians, Slovaks, Bohemians:

eight million. From the Balkans and the Middle East three million

more; Greeks, Macedonians, Croatians, Albanians, Armenians and

Syrians came to work in this new land to which a twelve dollar

steerage ticket gave them entry.

As workers and consumers

they flowed over the continent and each new pair of hands increased

our abundance.

By the beginning of the

Twentieth Century, immigrants were entering the country at the

rate of a million a year. Of these latecomers, many lacked the

means to make their way beyond the ports of arrival. Crowded

in the cities of the coast, stranded between the past and the

future. Bewildered. Exploited. They find it difficult to accept

the shifting forms they were expected to follow.

Yet for them too, in time,

the promises of America were fulfilled. They watched with wonder

as their children grew with the country. Moving forward into

free and open society they themselves had helped to create. In

times of crisis our doors are still open.Victims of tyranny and

oppression the world over find refuge among us.

We are today the most powerful

nation on Earth. Yet the challenges we face are more urgent than

any we have met in the past. Power alone will not solve them.

Power cannot tell us what to value; where to place our trust.

Power to share. There is no better place for Americans to find

their answers than in the heritage of our own unsettled and adventurous

past.

It is for us today to extend

the achievements of the immigrants whose descendants we are.

To continue their long struggle for dignity and freedom in a

world they could only dream of.

|

|