Source: US World's Fair Commission

Report, December 1960

|

| NEW YORK WORLD'S FAIR 1964 -

1965 CORPORATION |

| INTERIM REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

OF THE FAIR |

| TO THE PRESIDENT AND CONGRESS OF THE UNITED

STATES |

| SUGGESTING FOR

CONSIDERATION A PLAN FOR A PERMANENT |

| FRANKLIN NATIONAL

CENTER OF SCIENCE AND EDUCATION |

| TO HOUSE THE

UNITED STATES EXHIBIT AT THE FAIR |

|

|

|

INTRODUCTION

|

In order to facilitate action

on the vitally important United States Exhibit at the World's

Fair, the executives and directors of the Fair invited distinguished

consultants to prepare a plan of federal participation which

would provide a focal center, symbolize the basic theme and purposes

of the Exposition, serve as a guide to other American exhibits

illustrating the progress our nation has made, and serve as the

nucleus of a permanent Franklin National Center of Science and

Education paralleling in this field the area of culture represented

by the Lincoln Center for the Performing arts at Lincoln Square.

All signs point to a superlative

Fair at Flushing Meadow. It seems certain that exhibitors, domestic

and foreign, industrial and cultural, will send to us the very

best they have to offer. It becomes vital then that in the worldwide

competition of ideas and practical accomplishments, our central,

pivotal, national exhibit shall not, through lack of imagination

and financial support, be outclassed by others. The United States

Government exhibit should present graphically and convincingly

in impressive surroundings the immense strides we have made under

our free democratic system.

The distinguished servants whom

we consulted on this plan were:

- In Science:

- -Dr. Detleve W. Bronk, President of the

Rockefeller Institute and of the National Academy of Sciences-National

Research Council.

- -Dr. John R. Dunning, Dean of Engineering,

Columbia University

- -Dr. Lloyd V. Berkner, President, Associated

Universities, Inc.

- -Dr. William L. Laurence, Science Editor,

The New York Times, Chairman

-

- In Education:

- -Dr. John H. Fischer, Dean, Teachers College,

Columbia University

- -Dr. John W. Gardner, President of the

Carnegie Corporation of New York and of the Carnegie Foundation

for the Advancement of Teaching

- -Dr. Fred M. Hechinger, Education Editor,

The New York Times

- -Dr. Joseph E. Johnson, President, Carnegie

Foundation for International Peace

- -Dr. George N. Shuster, Past President,

Hunter College, Chairman

We have taken the liberty of

including in this interim report very preliminary graphic illustrations

of the plan we suggest and a rough estimate of cost.

It is unnecessary to add that

the location and character of this key federal exhibit are of

urgent importance because they affect and influence many other

features of the Fair which are advancing rapidly.

|

FRANKLIN NATIONAL

CENTER OF SCIENCE AND EDUCATION

SCIENCE EXHIBIT

|

Your committee is unanimously

agreed that the United States exhibit "involving primarily

our scientific accomplishments and our expectations for the near

future" should be the outstanding exhibit at the Fair. It

should be the finest of its kind, fully commensurate with the

greatness of America, not only as the country in which free men

attained the highest technological development and the highest

standard of living of any nation in history, but also as the

country in which science has made possible the evolution of a

free society in which every man achieved the highest dignity

and stature as an individual with the greatest opportunities

ever for the full development of his physical, intellectual,

spiritual and creative potential.

Not only has science made possible

in the United States the highest form of a free society, in which

every individual has an equal opportunity to realize to the fullest

extent all the innate potentialities of his endowment, it is

now playing the central role in the all-important task of defending

our free society against the greatest threat in its history.

A science exhibit officially sponsored by the leading nation

of the free world must make it clear to all the world that in

the great war of ideas we are now engaged, our greatest defensive

weapons are not atomic and hydrogen bombs but the mind of man

functioning in a climate of individual freedom.

While a United States science

exhibit should, understandably, involve our scientific accomplishments

it should not limit itself merely to our own accomplishments.

Fundamental scientific discoveries, upon which our great technological

achievements are based, have largely been made by scientists

of the free Western democracies, mainly Britain, France, Germany,

Italy and the Scandinavian countries. Our modern industrial civilization

began with the steam engine, invented by an Englishman, who made

use of basic laws of mechanics discovered by Galileo, an Italian,

and Newton, an Englishman. Newton's fundamental discoveries have,

in fact, laid the foundation for all the great contrivances of

the Machine Age. The principle of electromagnetic induction,

which made possible the dynamo and ushered in the Age of Electricity,

was discovered by Faraday, an Englishman. Another Englishman,

Sir J. J. Thomson, discovered the electron, the basis of all

the marvels of electronics -- radio, television, radar, automation,

02

|

rocketry, satellites, etc. Roenrgen,

a German, discovered the X-ray, one of the most powerful tools

to penetrate the mysteries of matter, as well as a powerful weapon

in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. Becquerel, a Frenchman,

discovered radioactivity, which opened the door to the Atomic

Age. Rutherford, an Englishman, discovered the nucleus of the

atom, citadel of the material universe, while another Englishman,

Chadwick, discovered the neutron, which opened the way to nuclear

fission, discovered by Otto Hahn, a German. Pasteur, a Frenchman,

discovered the bacterial origin of infectious disease and laid

the foundation for modern immunology, which revolutionized medicine

and public health. Fleming, an Englishman, discovered penicillin,

which opened the way for the antibiotics that have so far saved

more lives than were lost in both world wars. Mendel, an Austrian

monk, discovered the laws of heredity and laid the foundation

for modern genetics.

It is these fundamental discoveries,

made by men seeking knowledge for the sake of knowledge per se,

without an thought of its possible practical application, that

have opened the way for all our own scientific accomplishments,

which in turn, have made possible our way of life. Hence it is

obvious that a United States exhibit must, first of all, be a

history of ideas, showing how the inquisitive mind of man, given

full scope in an atmosphere of intellectual freedom, has, over

the centuries, and particularly since the advent of free institutions,

managed to make nature yield some of her most important secrets,

and how these triumphs of man's free mind have, in turn, made

it possible for all free men, and particularly the American people,

to harness the forces of nature to build a better life in an

environment vastly more suitable for man's needs, material, as

well as spiritual.

All the aforementioned fundamental

discoveries and many others in the fields of astronomy, physics,

chemistry, biology, genetics, geophysics, medicine, agriculture,

metallurgy, etc. upon which all our modern technological civilization

is based, should form important parts of the United States exhibit.

By taking advantage of all modern techniques of presentation

-- color motion pictures, television, transparencies, revolving

stages, with prominent scientists taking part in the demonstrations,

either in color

|

|

|

motion pictures or in person,

such exhibits could be made not only highly instructive, but

highly dramatic and entertaining as well.

There is no greater thrill than

that of the naked mind of man, with or without simple tools,

challenging nature to yield up some of her important secrets

and coming out triumphant after overcoming apparently insuperable

obstacles. The intellectual and spiritual exaltation, the religious

awe, that must have overcome Newton when he discovered the Law

of Gravitation, the ecstasy experienced by Einstein when he discovered

the principle of relativity (he was so overcome that he actually

took to bed for two weeks); the joy of Pierre and Marie Curie

the night they first saw the eerie light of radium in the abandoned

cadaver shed, after four years of back breaking labor, to take

but a few examples at random, could be made to live again in

the minds and hearts of the spectators at the exhibit, through

dramatic re-enactments of the original scenes.

Such exhibits will dramatically

demonstrate the following fundamental points:

- All modern technology has its

origin in fundamental discoveries made by inquisitive minds seeking

knowledge of nature.

- While pure science seeks only

knowledge, without any thought or practical application, every

scientific discovery eventually leads to far-reaching technological

developments for the improvement of man's lot on earth. Technology,

in turn, gives science new tools that make possible further fundamental

discoveries.

- All major discoveries in science

have led to further enhancement of the democratic way of life.

- Conversely, the democratic way

of life creates the best environment for the creative mind. This

is particularly true in the development of science and technology.

Without in any way resorting

to propaganda, the exhibit, as outlined, will make it clear that

not one of the major discoveries mentioned has come from either

Czarist or Communist Russia, or from Nazi Germany, or from any

other country without democratic institutions. The only major

technological development in Nazi Germany, the V-2 -- the first

practical rocket -- was based on principles developed by the

American, Robert Goddard, whose basic ideas were also lifted

bodily by the Russians

03

|

in the development of their sputniks.

In fact, all of Russia's technological progress is based on fundamental

scientific discoveries and technological developments made in

the free world, their technological development being largely

based on the technology of the United States.

All the aforementioned lead your

committee to the following conclusions:

- The United States Scientific

Exhibit should be the finest of its kind, exceeding in scope

the outstanding examples of equivalent institutions anywhere

in the world -- such as the Deutsches Museum in Munich or the

Palace of Discovery in Paris. It should, in fact, aim to become

one of the wonders of the modern world, fully representing the

spirit of America and commensurate with its greatness as the

leader of the free world. Properly planned, it could serve as

an expression of our faith in the future, as a potent weapon

in the war of ideas. In the present fateful struggle between

the concepts of a free society and totalitarian enslavement we

cannot afford second best.

- Such an institution must, obviously,

become a permanent part of our cultural heritage. It must be

housed in a monumental building that in itself would represent

one of the finest structures of its kind in the world, one that

would stand as a symbol of the modern free world in the same

manner as the great cathedrals of Europe symbolized the aspirations

and the faith of their builders and of the peoples of their day.

- We believe that such an exhibit,

and the structure in which it is housed requires a minimum of

seven acres, including exterior landscaping. A central location

is desirable as the United States Science Exhibit should be at

the center of the Fair, the hub from which all other exhibits

radiate. Such a central location, we believe, will enhance the

value of, and interest in, all other technological exhibits to

be presented by our leading industrial organizations, the technologies

of which are the results of basic discoveries in science. The

United States Science Exhibit would serve as the background that

will make all these industrial exhibits more understandable,

and hence more attractive.

|

|

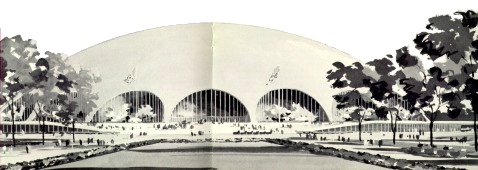

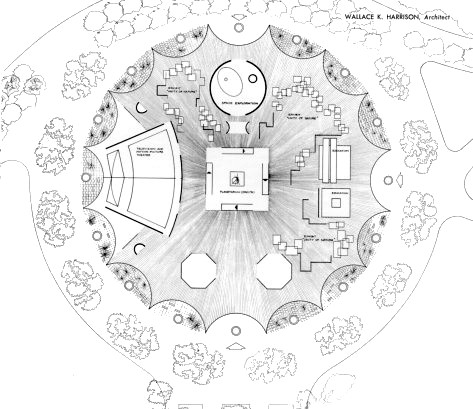

[Top: Artist's

conception of the proposed Franklin National Center of Science

and Education/Federal Pavilion at the 1964/1965 New York World's

Fair as designed by Wallace 9 Theater (left), Space Exploration

area (top) and a Planetarium (center). Display area called "Unity

of Nature" surrounds these major exhibit areas. And an area

for Education was reserved (right).]

|

|

|

The structure housing the United

States Exhibit should in itself be a most dramatic exhibit, a

dynamic symbol of the world of the future, showing the creative

mind of America at its best in one of its most original aspects.

The preliminary sketches for the proposed building were prepared

by Wallace K. Harrison.

After careful consideration,

your committee has come to the further conclusion that a United

States Science Exhibit of the dimensions outlined above would

require an appropriation by the Federal Government of $30,000,000

-- $20,000,000 for the building and $10,000,000 for the exhibits

it would house.

The institution on Flushing Meadow

must not be a museum of static displays, but a living dynamic

institution, a great cultural center, designed to instruct, to

enrich and to inspire all those who visit it, young and old,

university graduates and those of no more than a grammar school

education, It should instruct and at the same time entertain.

This great Center of Science and Technology, as we prefer to

call it, should be the equivalent of a great National Theater,

in which the leading actor is the human mind, groping and struggling

through the ages to learn the secrets of nature and to make man

at home in an orderly universe.

The Center would thus be above

all a revolutionary type of educational institution as well as

a new form of entertainment. Like a great repertory theater,

it should schedule special programs, daily or weekly, so that

a visitor having once come to it will want to visit it again

and again and will tell his friends to do likewise. It would

serve as a model for similar institutions in all other cities

throughout the country as well as in other parts of the world.

It could become a major attraction for conventions and tourists,

one of the showpieces of America.

As already stated, the Center

should take advantage of all modern techniques of presentation,

color motion pictures, television, revolving stages, etc. Motion

pictures in color should present in dramatic form the story of

the major discoveries of the fundamental laws of nature upon

which all our modern technology is based. The emphasis in all

these should be not on the "what?" but on the "how?",

the manner in which an idea emerged, not infrequently over the

course of centuries or millennia.

06

|

The exhibit should aim to give

the average person an outline of man's knowledge of the universe,

the infinite and the infinitesimal, the living and the non-living,

and how this knowledge was acquired. The motion pictures and

lectures by eminent scientists should serve to provide the background

for actual demonstrations showing the mind of great men in action.

These demonstrations should be

associated with personal participation on a do-it-yourself basis,

with the visitor himself performing some of the crucial experiments

that represent landmarks in the growth of ideas. The visitor

could be taught to weigh the earth, the moon and the sun; to

measure the velocity of light; and to determine on his own the

distance from the earth to the sun. Repeating the experiment

of Galileo, the visitor would rediscover for himself the law

of falling bodies; he could discover helium in the sun and determine

what other elements the sun is made of; he could repeat Faraday's

simple experiment that led to the Age of Electricity, and the

epoch making experiment by Hertz, in which he created the first

man-made electromagnetic wave, which ushered in the age of radio,

television and radar. These are only a few examples in which

the average person could be initiated into the fellowship of

the great discoverers through the ages.

Rather than being lost in a maze

of detail, the exhibit should stress the unity of nature and

the fundamental laws that govern it. It should be built around

several great general exhibits, all interrelated. One of these

should give the visitor a comprehensive view of the cosmos at

large, the universe of stars, galaxies and supergalaxies. Another

should give the story of the solar system and of the earth. The

story of matter and energy should be the subject of a third.

Another general exhibit should be devoted to the story of the

evolution of life on earth and the possibility of its existence

elsewhere in the universe. The nature of life and how it functions,

with emphasis on human development and physiology, should be

the subject of another. An exhibit showing how a humble monk,

Gregor Mendel, observing his peas in his garden, discovered the

laws of heredity operating throughout the entire realm of life,

from the lowest of bacteria to man, should be the starring point

for an exposition of the story of genetics.

All these great exhibits, however, should merely

|

|

|

serve as the background for the

story of America's contribution to science and technology, from

colonial times to the present. It should show how, building on

the discoveries of the past, the American creative mind transformed

a virgin continent into a New World which offered the greatest

opportunities for the individual to grow in freedom and to attain

the highest standard of living in history.

The exhibit should constitute

a great pageant of the great names in American science and invention

-- Franklin, Eli Whitney, Joseph Henry, Fulton, Morse, Bell,

Willard Gibbs, Michelson, Millikan, Edison and Tesla, to mention

but a few. It should show America's great contributions to the

development of the telegraph and the telephone, the automobile,

radio, television, and radar; the airplane, the helicopter and

the jet plane; its contributions to the science of nutrition,

to medicine and to surgery, to agriculture and transportation,

to the harnessing of great rivers, such as the Niagara and the

St. Lawrence with scale models of these giant dams.

Two of the major exhibits of

American technology should, of course, show our country's outstanding

contributions to the Atomic Age and the Age of Space. The atomic

exhibit should show the highlights of the great secret wartime

development that brought the Atomic Age into being. It should

show, among others, a model of the first nuclear reactor built

in the squash court at the University of Chicago, the first atomic

power plant in history. It should be climaxed with an actual

experimental swimming pool type of nuclear reactor, of the type

shown by the United States at the United Nations Conference on

the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva in 1955. Such a

reactor is absolutely safe and is highly spectacular. The exhibit

should also illustrate the great promise of atomic energy as

a vast new source of energy for industrial power, and as a most

important tool in agriculture, biology and medicine, which promises

to play a major role in the conquest of disease and the prolongation

of life.

The exhibit on the Space Age

should, first of all, provide a clear explanation of the fundamental

principles of the rocket and the principles that maintain a satellite

in its orbit. It should display models of the various American

satellites placed in orbit, their instrumentation and their purpose.

It should also

07

|

leave room for any new satellites

and new discoveries that will be made after the exhibit had been

set up.

In addition to providing a comprehensive

outline of scientific discoveries and technological developments

up to the present, the Fair should also provide a glimpse of

the immediate and the more distant future. It should show how

atomic energy promises to give mankind everywhere an abundant

source of energy for an abundant life, and how that will serve

as a vital factor in bringing peace to the world. It would show

mankind entering an era in which most major diseases will be

eliminated and the average lifespan will be significantly increased.

It should also show that, within the next two decades or so,

scientists hope to solve the problem of harnessing the fusion

energy of the hydrogen bomb as a limitless source of industrial

power, with the oceans of the world providing an endless source

of fuel.

Lastly, it should provide a glimpse of what further explorations

of outer space will bring in the future. Such a glimpse will

make the onlooker aware that we stand on the eve of some of the

greatest discoveries ever made, discoveries that may open vast

new horizons for mankind.

The exhibit as a whole must avoid giving the impression that

science and technology are purely materialistic. Science is the

outgrowth of the spirit of man, of his desire to know, to seek

the truth. Its technological fruits serve to make man free from

exhausting physical labor, to enable him to cultivate his spiritual

and creative powers, in short, to make him free. An understanding

of science should therefore give us faith in the future, for

science, by fostering the free mind, is the greatest enemy of

totalitarianism. The old maxim, "And ye shall know the truth

and the truth shall make you free" is still as valid as

it ever was

- Respectfully submitted

- DETLEV W. BRONK

- JOHN R. DUNNING

- LLOYD V. VERKNER

- WILLIAM L. LAURENCE

- Chairman

|

|

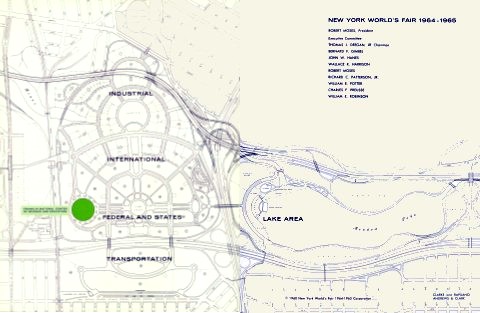

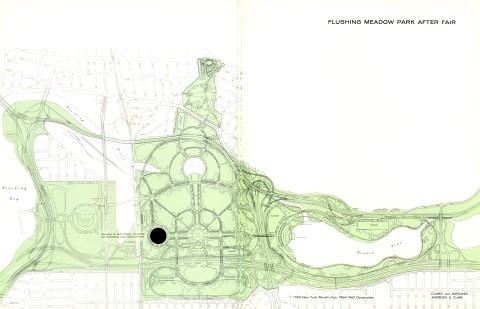

[Top: Site Plan

of the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair showing the proposed location

of the pavilion. Bottom: The Franklin Science Center would

be retained as a major feature of the post-Fair Flushing Meadows

Corona Park as illustrated in this diagram.]

|

|

ADDENDUM TO THE

REPORT OF THE SCIENCE COMMITTEE

EDUCATION EXHIBIT

|

As stated in the report of your

Committee on the United States Science Exhibit, the National

Center of Science would "be above all a revolutionary type

of educational institution as well as a new form of entertainment."

On further consideration, and

in the light of the valuable report of the Committee on Education

headed by Dr. George N. Shuster, and including Dr. John H. Fischer,

Dr. John W. Gardner, Dr. Fred M. Hechinger and Dr. Joseph E.

Johnson, it appears that the educational potentialities of such

a Center would be greatly enhanced by the incorporation of a

special exhibit that would tell in dramatic form, largely

through color motion pictures and closed circuit television,

the inspiring story of the development of the American educational

system, from the beginning to the present, with a glimpse into

the future.

Such an exhibit would not

require a special building, as one large hall, in the form

of an attractive and spacious auditorium, equipped with a modern

stage and screen and decorated with murals giving the highlights

of the story of education in America, would adequately serve

the purpose. Such a Hall of Education should form an integral

part of the Science Building. The Center could thus be named

the "Franklin National Center of Science and Education."

The educational section of the

Center should avoid any semblance of static museum-type exhibits.

The development of the educational system in America is one of

the glories of our land, a story of great human interest that

can be told in colorful and dramatic sequences in which the highlights

covering a period of more than three centuries could be reenacted

and made to live again. The story should tell how from the very

beginning the "things" our forefathers "longed

for, and looked after was to advance learning and perpetuate

it to our posterity." It should tell not only the American

people but the peoples from all parts of the world who will visit

the Fair, and in the years to come, that the ideal of universal

education for all, and not only for the privileged few, was fostered

in our country from the beginning; that this ideal became a keystone

of our democratic way of life, which gives every individual an

equal opportunity to develop to the fullest possible extent all

the innate talents within him. It should show that only in America

has this ideal been fostered, and is still being fostered,

12

|

not for the purpose of creating

robot-like servants of the State, but to give every individual

an equal opportunity to rise to his highest dignity as an individual;

to give life a higher meaning; to inspire to the fullest measure

a devotion to the highest values of existence; to instill in

every citizen love of God, of country and of his fellow men.

The spirit of American education,

that might well be expressed in an inscription on one of the

walls of the proposed Hall of Education, could best be illuminated

by the inspiring passage from New England's First Fruits, published

in 1643, telling the story of the founding of Harvard College

in 1636, a bare sixteen years after the landing of the Pilgrims.

"After God had carried us safe to New England, and wee

had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our liveli-hood,

rear'd convenient places for Gods worship, and settled the Civil

Government; One of the next things wee longed for, and looked

after was to advance learning and perpetuate it to our Posterity;

dreading to leave an illiterate Ministry to the Churches, when

our present Ministers shall lie in the Dust.

"And as wee were thinking and consulting how to effect

this Great Work, it pleased God to stir up the heart of one Mr.

Harvard (a Godly gentleman and a lover of learning, there living

among us) to give the one half of his Estate (in being in all

about 1700 pounds) toward the erecting of a Colledge; and all

his Library; after him another gave 300 pounds. Others after

them cast in more, and the publique hand of the State added the

rest; the Coledge was, by common consent, appointed to be at

Cambridge ( a place very pleasant and accommodate) and is called

(according to the name of the first founder) Harvard Colledge."

This inspiring story could well be dramatically re-enacted

in a color motion picture, to be written by one of our leading

dramatists. The film would show the Pilgrims in solemn conclave

at a Town Meeting which may well have followed the funeral of

one of their ministers. They would be shown discussing the need

for the advancement and perpetuation of learning, revealing their

"dread of leaving an illiterate ministry," and their

despair because of the lack of funds with which to accomplish

their purpose, when a young minister among them, John Harvard,

rises to announce his magnificent gift.

|

|

|

The story could then go on to

tell the early struggles of the young college for survival, how

the students paid their tuition with products of the farm --

cheese, milk, eggs and vegetables, which the faculty lived on.

It could show actual classrooms of the 17th Century, the methods

of teaching, student life, their games and their pranks. The

story could untold the role played by Harvard in the Revolutionary

War, in the Civil War, in World War I and II. Leading actors

could re-create some of the great teachers and personalities

of Harvard during its three centuries, making them live again

in their classrooms. Interwoven through the story should, of

course, be the landmarks showing the growth of Harvard from a

tiny "Colledge" of one small building to one of the

world's great institutions of learning with outstanding graduate

schools in Medicine, Law, Business, the Arts, the Sciences and

the Humanities.

Similar inspiring, intensely

dramatic stories could be told of our other great universities

-- Yale, Princeton, Columbia, to mention but a few. Many of these

dramatizations already exist. For example, during its recent

fund drive, Harvard produced a splendid motion picture, "From

the Age that is Past," shown so far only to a limited audience

of alumni, which should prove highly interesting to the public

at large.

Another dramatic and colorful

story could be told of the development of our great Land Grant

colleges and universities showing President Lincoln signing the

Land-Grant Act in 1862 and explaining its purpose; the development

of our great State Universities; the establishment of our great

institutions of learning for women; the world famous institutes

of technology, such as M.I.T. and Caltech; our great research

centers, such as the Rockefeller Institute; the unique Institute

for Advanced Study at Princeton; and our gigantic National Laboratories,

serving groups of universities, at Brookhaven, N. Y., Oak Ridge,

Tenn.; and Argonne, near Chicago.

By means of closed circuit television,

the visitor at the Center would be permitted to enter classrooms

in several of our leading universities, showing education in

action. He could be made a participant in some of the sudents'

extra-curricular activities, watch rehearsals and actual performances

of their dramatic societies, debating teams, glee clubs. he could

sit in at a typical "bull-session" among undergraduates

and made to feel as one of them.

One of the special features of

the education exhibit could be a re-enactment of some of the

memorable football games

|

of the past, bringing back to

life, or restore the youth of, some of the legendary names in

football history. This feature of the exhibit should, of course,

show present day athletic activities, illustrating the fact that

American education is designed to meet the needs of the whole

man, body, mind and spirit.

A major part of the exhibit should

be devoted to a dramatic presentation of the development of the

elementary school, the high school and the kindergarten, with

living subjects playing their respective parts in the proper

environment. This group of exhibits, all in color motion pictures,

should bring back to life the original red school house, with

all the trimmings. It should show the teachers and the children

in the dress of the period, and the manner in which the three

R's were taught. It should graphically depict how this little

red school house gradually developed over the years into the

modern elementary school and high school. These exhibits also

should show typical classrooms in action, with living actors

playing the part of the teachers and real children acting as

the pupils. Whenever possible actual modern classrooms should

be entered by means of closed circuit television.

One of the major aims of this

exhibit would be to illustrate the development of the art of

teaching from its crude beginnings to its modern advanced techniques.

This could be done by showing classrooms at various periods in

our history and the methods used in teaching certain subjects.

The exhibit could be climaxed with a present day version of

the meeting of the Pilgrims that led to the founding of Harvard.

In the modern version we would have (in color motion picture)

a group of distinguished educators, including the presidents

of a number of our leading institutions of learning, expressing

their fears for the future and affirming once again that "the

things we long for, and look after, is to advance learning and

perpetuate it to our posterity." In this sequence should

be outlined, in the words of the educators, the great problems

now facing American education, stressing the fact that we are

now engaged in a fateful struggle for survival that requires

the training of our best minds, through a system of universal

education designed to meet effectively the great challenge of

our day.

Respectfully submitted

WILLIAM L. LAURENCE

Chairman, Science Committee

|

|

|

|

December 5, 1960 |

|

|

Webmasters

note...

On March 15,

1958, a meeting was held in Washington D.C. that included representatives

of the US Congress and the scientific community. "The consensus

of the meeting was that if the backers of the Seattle Exposition

[of 1962] were serious about having a large popular

science exhibit, the scientific community would eagerly support

them. However, it was emphasized that the exhibits must deal

with science not in terms of technology, but as an adventure

of the mind, as man's effort to understand the universe, and

must appeal to the general public rather than the spiritualist."

-- U.S. Science Exhibit, Seattle World's Fair, Final Report,

March 15, 1963.

It is curious

then that the New York World's Fair proposed to the Federal Government

that they sponsor a major Science Exhibit at their World's

Fair. Exposition organizers knew that planning had been underway

for the Science Exhibit in Seattle for over two years when they

made their proposal on December 5, 1960. In fact ground had already

been broken for the U.S. Science Pavilion in Seattle four months

earlier and construction was proceeding.

Why the duplication

of theme? The United States pavilion at the Brussels World's

Fair of 1958 also relied heavily on Science to attract crowds

and show off U.S. superiority in the Cold War. Did Cold War attitudes

in the early sixties dictate New York should follow it's predecessor

Fairs in using Science as a weapon in a war of exhibits? Did

New York wish to take advantage of the popularity of Science

to ensure crowds; thinking that a Space Age Fair without a Science

Center as a base was doomed to fail? Was it a way for the Fair

to get the Federal government to pay for the Hall of Science

they desired for post-Fair Flushing Meadows Park? Or were they

simply afraid of being out-classed by a much smaller city's Fair?

|

|