|

Legend has it that they do everything big in Texas.

Well if that's really the case then Angus G. Wynne Jr. must have lived a true Texas life. For Wynne was a guy who really did dream big. Amusement park fans remember Angus as the visionary who created America's first truly successful regional theme park: Six Flags Over Texas.

The folks around Arlington, Texas (Six Flags' hometown) remain grateful to Angus for several reasons. One is that world-class theme park that he built right at their doorstep for the townspeople to play in. The other is the Great Southwest Industrial District, the 8,200-acre industrial park that Wynne built nearby. That park is home to over 3,000 companies, providing thousands upon thousands of jobs for the local community for over 40 years now.

But World's Fair enthusiasts ... well, they have a somewhat different take on this Texan. They associate Wynne's name with the legendary Texas Pavilions at the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair - an exhibit that's considered somewhat infamous and mysterious these days because so few Fairgoers ever got to see the thing.

According to press accounts of the day, it really must have been something to see. A multi-million dollar showplace featuring what many have called the greatest stage show ever produced. Yet the Texas Pavilions, which had originally been slated to be up and running for both years of the Fair, barely managed to limp through one season. The stage show? It didn't even last that long. It shuttered after less than 100 performances.

What exactly went wrong here? For nearly 40 years now, stories have been circulating about why the Lone Star State's exhibition fared so poorly at the Fair. Some blame the Texas Pavilions' remote location for the low attendance levels. Still others suggest that anti-Texas sentiment may have played an important part in the exhibit's tepid turnout.

A few folks hold Wynne personally responsible for the Texas State pavilion debacle. But many more suggest that World's Fair President Robert Moses should shoulder most of the blame. After all, Moses was the man who kept promising that his Fair would be different. That this international exhibition would have record levels of attendance which prompted businessmen like Wynne to mount elaborate and expensive exhibits for crowds that never came.

These are the sorts of questions that continue to bedevil 1964/1965 New York World's Fair fans even today: What were the Texas Pavilions really like? Just how good was this legendary stage show? And why really did the exhibit shut down after just one season?

These are questions that have gone unanswered. Until now.

Through interviews with folks who actually worked on the Texas Pavilions as well as conversations with Wynne family members, a more accurate picture of that long closed '64 World's Fair exhibit is now emerging. Of course, to fully understand what went on (and - more importantly - what went wrong) with the Texas Pavilions, you need to know something about the man who build them: Angus G. Wynne Jr.

A man who learned the hard way that life's not fair. Particularly when you're producing a show for the FAIR.

Source: www.Alchetron.com - The Free Social Encyclopedia for the World

|

|

| Angus Wynne Jr. c. 1947 |

These days, most stories written about Wynne tend to dwell on the important role he played in the creation and construction of the first three theme parks in the Six Flags chain. Sure, Six Flags Over Texas (which opened in 1961), Six Flags Over Georgia (1967) and Six Flags Over Mid-America (1971) are all pretty impressive enterprises but they pale in comparison to everything else Angus accomplished in his lifetime.

Putting it simply, Wynne was a visionary. In the late 1950s, he looked out at that large patch of dirt that separated Dallas and Ft. Worth and saw the future. A time when these two Texas towns would quit their squabbling and grow together to form a vast metroplex. Since this spot in the middle of nowhere was roughly where the two municipalities would eventually collide, that's where Angus and his partners in the Great Southwest Corporation decided to kick start the area's economy by building a large industrial park.

It was tough going those first few years. The GSC team threw up a few buildings on spec and then tried to get area businesses to move into them. But Dallas organizations turned their noses up at the development claiming that it was too close to Ft. Worth. Ft. Worth folks thumbed their noses at the industrial park too, thinking that it was far too close to Dallas.

As 1960 rolled around the Great Southwest Corporation was vacillating about what to do next with this piece of property. Some members of the board were pushing for construction of another set of spec buildings, hoping that the company would eventually be able to rent these out and get some sort of return on their investment.

Wynne had another plan in mind. Noting the immense amount of money that Walt Disney was making off of Disneyland in Southern California, Wynne proposed building a theme park out on that slab of land that GSC owned between Dallas and Ft. Worth. To Angus' way of thinking, here finally was an idea that was guaranteed to generate some cash flow for the company.

This was not a popular proposition with a lot of the other members of the Great Southwest board. Wynne had to twist a few heads and arms before he finally got their approval to go ahead with his amusement park project.

Construction began in October of 1960. It continued at a whirlwind pace for the next 10 months as construction crews worked 'round the clock to turn a scrub covered, rattlesnake infested hillside into a spectacular family fun center.

Finally in August of 1961, the Lone Star State's first theme park - Six Flags Over Texas - threw open its doors. Those first few weeks though, only a small number of folks trickled in to sample the various rides, shows and attractions that Wynne's team had set up on the outskirts of Arlington, Texas.

-

- SIX FLAGS OVER TEXAS

- Aerial View of the Park from the 1960s

|

|

|

Source: Official Postcard from www.lonestarpolitics.wordpress.com

|

This last bit of news sort of concerned Wynne. You see, in order to secure the financing necessary to expand his $3.5 million theme park, Six Flags had to get at least 400,000 paid admissions during the first year of operation. But the park's first year of operation wasn't even really a year. It was just a couple of weeks; August through Labor Day.

Happily, those first few folks who visited Six Flags Over Texas during those early week's operation must have really talked up the joint. For word of mouth built and, by the end of the park's first season, 500,000 people had pushed their way through the turnstiles.

Those 500,000 paid admissions gave Wynne the freedom he needed to grow his little Arlington, Texas park into a world-class operation. Over the next two years, Wynne added tons of new shows and attractions to Six Flags Over Texas. This in turn inspired record numbers of people to come out and see the park. Which resulted in huge profits for the Great Southwest Corporation.

-

- SIX FLAGS OVER TEXAS

- Post Card Folder

|

|

|

Source: Official Postcard from Six Flags Over Texas c. 1960s

|

Of course, all this success quickly brought Wynne to the attention of the Texas elite. Particularly then-Vice President Lyndon Johnson and Texas Governor John Connally, who were then casting about for someone to take charge of the state's efforts to develop an exhibit for the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair.

Being as full of Texas pride as they were, Johnson and Connally wanted the Lone Star State's exhibit at the Fair to be the biggest and best of the bunch. That's why they eventually decided to try and recruit Angus.

After all, here was this innovative real estate developer who had taken a scrub-covered hillside in Arlington and turned it into the Texas version of Disneyland. Surely Wynne was the guy who could take a corner in Queens and turn it into something that would make all Texans proud.

Wynne was, of course, flattered when Johnson and Connally personally sought him out and offered this opportunity. After a little hemming and hawing Wynne finally agreed to step up to the plate and personally supervise the Texas State pavilion project. After taking a temporary leave of absence from Great Southwest Corporation, Angus then made a call to his old buddy, Randall Duell.

And who exactly was Randall Duell? Randall was a former MGM art director (Did you ever see that studio's 1952 release, "Singin' in the Rain"? Thought that the sets for that film looked snazzy, didn't you? Well, Duell designed those along with the sets for dozens of other classic MGM productions of the 1940s and 1950s) who had done most of the design work for the shows and attractions at Six Flags Over Texas.

Given the many sophisticated films Randall had worked on during his stint at MGM, Wynne felt certain that Duell was the guy who could come up with a show that would make all Texans proud as well as appeal to those snooty New Yorkers. The big questions was: Just how do you go about whittling the great state of Texas down so that all of its rich history and culture could fit inside of some itty-bitty building?

The obvious answer here is: You can't. Which is why Randall sold Wynne on a really wild idea. Texas' exhibit wouldn't be housed inside of a single building but, rather, Wynne would stage a fitting tribute to the Lone Star State by building seven different Texas-themed pavilions that would be spread out over a three acre site.

-

- THE TEXAS PAVILIONS & THE MUSIC HALL

- 1964-1965 New York World's Fair

|

|

|

Source: Official Publicity Photo, New York World's Fair Corporation, Courtesy Craig Bavaro Collection

|

To be honest, this concept borrowed quite a bit from Six Flags Over Texas (the theme park was divided into six different "lands," each area themed around a nation whose flag had flown over Texas at one time or another). Which is probably why Wynne immediately warmed to the idea.

Duell's plans called for seven separate pavilions, each celebrating a different aspect of Texas' colorful culture and history. Among the areas that Randall wanted this exhibit to touch on was the great impact that Spanish explorers and Mexican settlers had had on the region, the terriory's Confederate heritage as well as the state's rough-and-tumble phase, way back when Texas was just a republic.

The Lone Star State's wild west days would be celebrated in the Texas Paviions' Frontier Palace restaurant complex. Guests would enter the eatery through an exterior facade that was made up to look like an elegant prarie home circa the 1880s. Inside, they'd find a 500-seat dinner theater designed to look like an authentic frontier saloon.

-

- THE FRONTIER PALACE

- One of the Texas Pavilions at the New York World's Fair. A bit of the old west, guns, girls, un all.

|

|

|

Souce: Orfficial Postcard by Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY

|

Inside this rustic looking restaurant, chuck wagon steak was the big item on the menu while can-can girls would provide the entertainment. For those who were thirsty for a little gratuitous violence, occasionally two feuding waiters would settle their differences by pulling out their pistols and firing at each other. Right over the heads of the Frontier Palace's patrons! (Don't worry though folks. those waiters were only using cap pistols.)

Of course, the achievements of modern Texas would also have to play an important part in the exhibits that were being presented at the state's New York World's Fair pavilions. That's why Duell wanted to celebrate the Houston/Gulf Coast area and its importance to the aerospace industry by getting NASA to agree to dislay its latest creation: a full-scale version of the two passenger Gemini space capsule.

Randall also wanted the state's oil industry to put together a display that highlighted the cutting edge technology that 1960s era "wildcatters" used while drilling for crude oil. As for Texas' cattle ranchers ... Well, that's kind of an interesting story.

You see, back in the mid-1950s, Prince 105TT - a prize-winning steer that the Wynne family had raised at its Four Winds ranch - was named "Best in Show" at the Texas State Fair. To commemorate this great event the family decided that Prince 105TT should get the royal treatment.

Which is why the Wynnes treated this prize-winning steer, plus a heifer and a couple of calves, to a stay at the Menger Hotel in Tyler, Texas. The family rented out the Presidential Suite and, after setting down a few bales of hay, moved Prince and his entourage in.

This must have been a really remarkable sight, for Wynne family members still talk about it even today. Angus must have mentioned it to Randall once or twice for the desinger decided to pay tribuite to this odd piece of family history by replicating Prince 105TT's stay in the Presidential Suite as a display at the Texas Pavillions.

Sure, the official 1964 New York World's Fair guidebook describes this particular exhibit, where an enormous Brahman bull was kept corralled inside an elegant French bedroom, as being symbolic of the pampered lives that modern livestock supposedly live. But Wynne family and friends knew better and they supposedly got a real kick out of seeing this odd little moment recreated in Queens.

And what theme could be used to tie together all the extremely different elements that Randall wanted to include in his Texas Pavilions design? "Friendship at the Farm." To re-enforce this concept Duell proposed bringing 400 bright-and-smiling young Texans up north to work at the exhibit so that those native New Yorkers would be sure to get an authentic Texas greeting from an authentic Texan the next time they moseyed back into this neck of the woods.

Of course, with the hope that all this Texas style hospitality might inspire Fairgoers to go visit the real thing, Randall made sure that a Texas Tourism paviion figured prominenetly in the exhibit's plans. This light, airy structure would direct potential tourists to the many wonders to be found in the Lone Star State (with a particularly large plug for Wynne's other entertainment enterprise, Six Flags Over Texas).

But what about all those sophisticated New Yorkers? Those types of folks who were sure to look down their noses at watiers who played with cap pistols and/or bulls that were being displayed in bedrooms. What was there at the Texas pavilions to entertain the snooty set?

As a sop to the snobs Duell proposed taking something that Wynne was already doing at his theme park, i.e. a Broadway-style musical production, and radically expanding on that idea. If Wynne really did want to win over those New York sophisticates, then why not recruit some theater professionals to produce the ultimate Broadway show - a lavish revue that celebrated the best shows that had been presented on the great White Way over the last 100 years?

That's just what Wynne did. Working through the offices of Compass Productions, Wynne recruited top talent to put together this proposed production. First of all, he landed veteran television and theatrical prducer George Schaefer (best known as the man behind the original Broadway production of that Tony Award winner, "The Teahouse of the August Moon") to ride herd on this Best-of-Broadway revue.

Schaefer in turn would hire one of Broadway's best, Morton Da Costa, to serve as director for the show that was being prepared for the Texas State pavilions. Though mostly unknown today, Da Costa was considered a major talent back in the 1950s and 1960s. These days, Morton's probably best remembered as the man who directed both the original Broadway production as well as the movie version of Meredith Willson's classic, "The Music Man."

George then went about putting together a crack creative team to assemble the ambitious musical revue. That's why he hired Tony & Pulitzer Prize winers Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harrick (who would go on to even greater fame in September of 1964 when their next smash hit, "Fiddler on the Roof," opened on Broadway) to create a book for the revue. The songwriting team also contributed several specialty numbers as well as came up with a suitable title for this ambitious extravangaza.

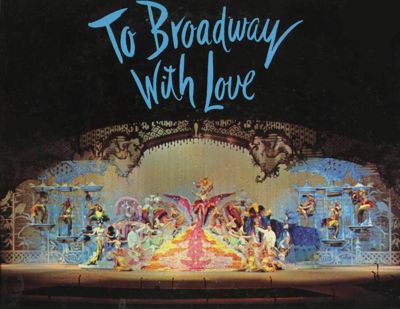

And what title did Bock and Harrick come up with for this Texas-sized revue? Predictably enough, it was "To Broadway With Love."

|

|

|

|

Souce: Original Cast Album, "To Broadway With Love"

|

So what was the show like? Well, if you're really interested, I suggest you chase down a copy of the "To Broadway With Love" original cast album. This vinyl LP, recorded by Columbia in early 1964, presents an accurate aural picture of the elaborate extravaganza. Just as Duell had originally suggested, the revue quickly runs through 100 years of Broadway history by presening many famous numbers from long-forgotten shows. There's lots of George M. Cohan in here, a big chunk of Iriving Berlin, even some Rodgers and Hammerstein tossed in for good measure.

As for the cast of the show, Schaefer and Da Costa assembled a very talented troupe. Unfortunately, due to the fact that "To Broadway With Love" was supposed to be presented three times daily (3:00, 7:00 & 9:30 p.m.), George and Morton were unsuccessful in their efforts to recruit a big name entertainer to serve as the headliner for the Texas Pavilions' stage extravaganza. So the pageant ultimately became a no-name show. (Though there was one member of the chorus, a young dancer named Goldie Hawn, that would eventually go on to considerable fame and fortune in Hollywood. But only after Ms. Hawn gave up her dream of becoming a Broadway hoofer and headed west to find work in television.)

Of course, a show this ambitious needs a lavish setting. That's why Wynne pulled out the stops while creating the centerpiece of his New York World's Fair exhibit, the Texas State Pavilions' Music Hall. Truthfully, no expense was spared on this project. This 2,400-seat facility was built with a stage that was over 70 feet wide. All of the lighting rigs and stage devices used in the show were state-of-the-art (circa 1964 of course).

-

- THE MUSIC HALL

- of the Texas Pavilions at the New York World's Fair

|

|

|

Souce: Orfficial Postcard by Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY

|

The Muisc Hall also featured an Executive Bar and Lounge area (whcih was alledgedly supposed to serve as an American Airlines Admirals Club during the run of the Fair, giving all those tired frequent flyers a cushy place to rest their feet after spending a day exploring all the wonders to be found on Flushing Meadows). And, for those folks who desired a more elegant way to view a performance of "To Broadway With Love," the theater had its Champagne Circle, a series of private boxes that were located on the Music Hall's second and third levels. Inside of these elegantly appointed enclosures (the boxes' decor was designed by noted Dallas interior decorator, William P. McFadden), patrons were free to sip cocktails while they enjoyed the show.

Unable to control his enthusiasm for the project, Wynne poured millions from his own fortune into the construction of the Texas State Pavilions. Sure, there was some risk involved, But given the millions of people who were expected to attend the New York World's Fair during its two year run, Wynne thought it was safe to assume that this particular investment would pay off in a big way.

After all, wasn't Fair President Robert Moses predicting that over 70 million people would come to Queens just to attend the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair? If even a fifth of these folks made their way back to the Texas Pavilions and took in a show, Angus would be rolling in dough.

Best of all, Wynne had built the Texas Pavilions at the urging of Lyndon Johnson and John Connally. That meant that the Vice President of the United States and the Governor of Texas now each owed Angus a favor. Those made for some pretty impressive markers for the former Texas businessman to cash in later in life.

So, in spite of his initial misgivings, Wynne went full speed ahead on this project. Ground was broken for the Texas Pavilions complex in early 1963, with Governor Connally himself showing up to help the Wynnes turn that first symbolic spade of earth.

To help publicize his state's participation in the Fair, Connally declared Bobo, a 2,000 pound Brahman bull, an official Texas goodwill ambassador to the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair. Cowboy Jerry Cotten then climbed on Bobo's back and rode the Brahman all the way from the Lone Star State to the Texas Pavilions at Flushing Meadows. Reporters regularly filed stories on the unusual pair wondering if Jerry and Bobo would be able to survive the 2,000 mile trek and/or whether the bull and his rider would arrive in time to enjoy the Fair's opening day festivities in April of 1964.

Unfortunately Bobo wasn't the only bull that Wynne had to deal with during the construction phase of the Texas Pavilions. Moses, ever fearful that New York's construction unions would intentionally delay the opening of his Fair if they didn't get their piece of the pie, let them get away with charging ridiculous rates for all work that was done on the international exhibition's pavilions. As a result, union carpenters who worked on building the musical were paid $23 per hour.

And that's not the overtime rate, folks. That's actually the flat base pay rate paid for on-site construction done at Flushing Meadows, (minus, of course, the 50% kickback you were expected to hand over to your shop steward, the guy who actually landed you this cushy gig).

This plus the demands of the steelworker's union (which insisted that New York State regulations prevented them from doing any on-site steel bending while working in Queens) resulted in tremendous cost over-runs on the Texas Pavilions. When news of this got back to Angus, he was understandably concerned about the spiraling costs of the project.

-

- GATEWAY TO MEXICO Patio

- The Texas Pavilion - New York World's Fair

|

|

|

Souce: Orfficial Postcard by Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY

|

But then, after he attended a dress rehearsal for "To Broadway With Love," Wynne became convinced that his World's Fair entry was going to be a winner. He felt certain that the Texas Pavilions' elaborate stage revue would win over the city's toughest audience (New York City's theater critics) that would lead to rave reviews. Whcih would lead to large crowds deliberately seeking out the entertainment to be found at the Lone Star State's exhibition. Which would translate into huge food and beverage sales at the Texas Pavilions' concession stands. Which meant Angus' semingly risky NYC investment would eventually pay off in a big way.

Well, the first part of Wynne's plan came true. The New York theatre critics really did love "To Broadway With Love" calling the Music Hall's live stage presentation one of the very things to be seen at the Fair.

A "Don't Miss" attraction. Thrilled with the pageant's critical reception, Wynne stood back and waited for the crowds to come rushing in ...

... but the crowds never came.

To be honest, attendance was a problem at the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair almost from Day One. Moses had told the press and Fair participants that he expected his international exhibiton to have many "quarter million days." Meaning that Robert thought that during the course of the Fair there would be numerous days where at least 250,000 people would push through the turnstiles at Flushing Meadows.

The trouble is that, at least during the Fair's crucial first few weeks of operation, those "quarter million days" never came. During the months of April and May there were times that only 40,000 to 50,000 folks made the trip out to Queens. This meant that the Fair wasn't even coming close to meeting Moses' attendance projections.

This was bad news for most World's Fair participants. But truly disastrous news for Angus Wynne Jr. He kept hoping that his Texas Paivlions experience would be a duplicate of the early days of Six Flags Over Texas. Where, for those first few weeks, only a handful of people came. Once word of mouth spread the crowds would eventually come rushing in.

But that never happened. For most of the Spring of 1964 the crowds never really came out for the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair.

Even when a moderate sized crowd of 100,00 to 150,000 entered the Fairgrounds at Flushing, very few of these folks ever seemed to make their way back to the Texas State Paviions complex. Why for? Well, some people have theorized that the Lone Star State's lack-of-traffic problems simply boiled down to the No. 1 rule of real estate: Location, location, location.

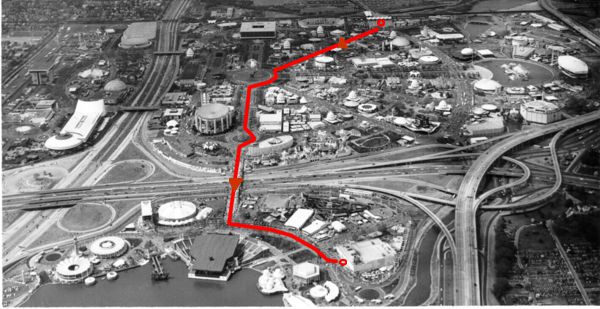

Putting it bluntly, Wynne's Texas Pavilions seem to have been built in the most remote location to be found at the Fair. A guest arriving at the Fair's main entrance who wanted to catch a performance of "To Broadway With Love" would first have to hike down New York Avenue. He'd then have to cross the Court of States, go around the Unisphere, down the Court of Nations before he reached Harry Turman Promenade. Then the poor slob had to find the pedestrian footbridge that would allow him to cross over the Long Island Expressway, which would eventually lead him into the Lake Amusement Area. That's where, in the uppermost corner of this far-off region that bordered on Meadow Lake, the exhausted visitor would finally find Angus' Texas Pavilions.

Of course, in order for your typical tourist to follow this path (the most direct route to the Lake Amusement Area as well as the Texas Pavilions) they would have to walk by dozens upon dozens of other tempting attractions. Other enormous paviions whose sponsors weren't asking guests to fork over $2 to $4.80 (the going rate of a seat to most performances of "To Broadway With Love") to see the presentation. These give-it-away-for-free shows really made life rough for the Fair's pay-to-view attractions like Wynne's Music Hall show.

-

- LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

- The route a Fairgoer would take from the Fair's Main Entrance to the Texas Pavilions & The Music Hall.

|

|

|

Souce: Orfficial Publicity Photograph, New York World's Fair Corporation [path drawn for illustration purposes]

|

It's also been suggested that other unfortunate, unforseen circumstances, beyond the Texas Pavilion's seemingly remote location, may have played a large part in the lack of attendance seen at the Lone Star State's exhibits. After all, just six months prior to the opening of the Fair, President John F. Kennedy was killed in Dallas.

Could the small number of folks who turned out to see Wynne's assortment of attractions seriously be interpreted as some sort of anti-Texas backlash? Personally, I find this idea kind of far-fetched. But Luther Clark, a longtime Wynne associate who actually rode herd on the construction of the '64 World's Fair Texas Pavilions, insists that anti-Texas sentiment really did play a huge part in the failure of Angus's New York City attractions.

"Back then, the people of New York just hated Texas because we were the guys who'd killed the President," Clark explained. "Those folks wanted nothing to do with Texas. Which was why all of our attractions for the Fair only ran for one year."

Mind you, some of the Texas Pavilions' shows and exhibits didn't even last that long. In spite of its great reviews and ample publicity (The 1964 Emmy Awards even managed to work in a sizable plug for Wynne's theatrical revue. Though the majority of that year's ceremony was being broadcast from the Hollywood Palladium, a good portion of that night's program was presented, via live remote feed, right from the stage of the Texas Pavilions' Music Hall.) "To Broadway With Love" shuttered after only 97 performances.

Everyone who actually saw the show back in the Spring of 1964 thought that "To Broadway With Love" was a wonderful piece of entertainment, something well worth going out of your way to see. But since so few Fairgoers seemed willing to make the trek out to the Texas Pavilions (during a typical performance of "To Broadway With Love," Wynne considered himself fortunate if he was able to fill even a tenth of the cavernous Music Hall's 2,400 seats), Wynne really had no choice but to shut the show down.

The end came pretty quickly after that. Once "To Broadway With Love" closed the Texas Pavilions lost the attraction that had served as the primary focus of the exhibit's ad campaign. Without that show to serve as the carrot that tempted people to take that long walk all the way out to the Lake Amusement Area, those small crowds got even smaller.

-

- INTERSTATE HOSTS GIFT SHOP

- Texas Pavilions at the New York World's Fair

|

|

|

Souce: Orfficial Postcard by Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY

|

Partially as a face-saving gesture, but mostly as a courtesy to the 400 young Texans who had relocated to the Big Apple to help operate his attractons, Angus tried to keep the other pieces of the Texas Pavilions up and running througout the rest of the Fair's 1964 season. However, in order to do this, Wynne had to accept loans from the World's Fair Corporation itself.

The trouble is there was just no way that Wynne was ever going to be able to repay the Fair Corporation. Wynne had blown through much of his own personal fortune during the initial construction phase of the Texas Pavilions. So when the Fair Corporation finally came calling looking to get its loans repaid, Angus had no money to give them. In the end, Wynne was forced to declare bankruptcy. Which was why, when the Fair's books were finally audited in December, 1965 by then New York City Comptroller (and eventual New York City Mayor) Abe Beame, Angus Wynne, Jr. still owed the World's Fair Corporation $1,348.276.57.

When the Fair ended its first season in October, 1964, the few remaing exhibits at the Texas Pavilions closed for good. The following year, World's Fair officials tried to boost attendance by setting up some carnival rides on the 3-acre lot that used to play host to the Lone Star State's exhibits. but this meager assortment of new attractions still wasn't enough to get people to hike all the way back to the Lake Amusement Area.

Wynne's return home to Texas after the Fair left the man with a lot of mixed emotions. Wynne was obviously embarrassed at having had to declare bankruptcy (though his friends, in an effort to soften the blow, threw him a bankruptcy party where they all came dressed as bums). Wynne was also extremely angry with Robert Moses and would remain so for the rest of his life. He felt that the way that the Fair President had oversold the event - proposing record attendance levels that the Fair never even came close to achieving - had played a huge part in the failure of his Texas Pavilions.

But, mostly, Wynne was anxious to get back to work; to take up the reins of the Great Southwest Corporation again. Under Wynne's command, GSC grew to be one of the nation's biggest real estate development companies. During the late 1960s, Angus' company built hundreds of apartment buildings, dozens of industrial parks and, of course, two great new theme parks: Six Flags Over Georgia and Six Flags Over Mid-America.

Though the Great Southwest Corporation would eventually sell off all of its theme park holdings in 1972, the folks at Six Flags never forgot Wynne's contribution to their company. Which is why, in the Confederate section of Six Flags Over Georgia, there's a memorial plaque that reads, "Dedicated to the memory of Angus G. Wynne, Jr. Innovator and friend. Founder of Six Flags Over Georgia. We dedicate ourselves to providing the wholesome blend of family entertainment which was Angus G. Wynne, Jr.'s dream come true."

Memorial Plaque?! Yep. Did I forget to mention that Wynne died back in 1979? This much respected businessman may have passed on, but the cities of Grand Prairie and Arlington, Texas still think fondly of old Angus and all the fun and prosperity he provided for the Lone Star State. Which is why, a few years back, family friends and local officials working with the Texas Department of Transportation decided to honor Wynne's memory by renaming busy Texas Highway 360 the Angus Wynne Jr. Freeway.

It is, rather fittingly, the major highway that you have to ride on if you're taking a trip out to Six Flags Over Texas. More pointedly there isn't a single exit ramp off of the Wynne that will take you anywhere near New York City.

Which is just the way Angus would have liked it, I'm betting.

|