We must exercise every ingenuity

to reconcile differences by simple, friendly human contacts away

from protocol, diplomacy and debates over ideologies which are

the functions of the chancelleries and the United Nations. This

is our opportunity at Flushing Meadow in 1964 and 1965.

- Robert Moses101

MURAL OF A REFUGEE*

|

- Before you

go,

- Have you

a minute to spare,

- To hear a

word on Palestine

- And perhaps

to help us right a wrong?

-

- Ever since

the birth of Christ

- And later

with the coming of Mohammed,

- Christians,

Jews and Moslems, believers

- .....in one God,

- Lived there

in peaceful harmony.

-

- For centuries

it was so,

- Until strangers

from abroad,

- Professing

one thing, but underneath,

- .....another,

- Began buying

up land and stirring up the

- .....people.

-

- Neighbors

became enemies

- And fought

against each other,

- The strangers,

once thought terror's victims,

- Became terror's

fierce practioners.

-

- Seeking peace

at all costs, including the

- .....cost of justice,

- The blinded

world, in solemn council, split

- .....the land in two,

|

- Tossing to

one side

- The right

of self-determination.

-

- What followed

then perhaps you know.

- Seeking to

redress the wrong, our nearby

- .....neighbors

- Tried to

help us in our cause,

- And for reasons,

not in their control, did not

- .....succeed.

-

- Today, there

are a million of us,

- Some like

us, but many like my mother,

- Wasting their

lives in exiled misery

- Waiting to

go home.

-

- But even

now, to protect their gains ill-got,

- As if the

land was theirs and had the right,

- They're threatening

to disturb the Jordan's

- .....course

- And make

the desert bloom with warriors.

-

- And who's

to stop them?

- The world

seems not to care, or is blinded

- .....still.

- That's why

I'm glad you stopped

- And heard

the story.

|

|

The New York World's Fair opened on April

22, 1964. By April 23, the Fair's theme of Peace Through Understanding

was already coming into question, as officials from the American-Israel

Pavilion lodged a complaint about an item in the Jordan Pavilion.

The item of controversy was a mural which was displayed near

the exit of Jordan's exhibit, depicting a young Arab refugee

and his mother. The mural was inscribed with a poem which commented

on the refugee situation in Palestine. "Before you go, have

you a minute more to spare to hear a word on Palestine and perhaps

to help us right a wrong?" the poem begins. It goes on to

say that the people of the region lived in peace and harmony

until "strangers from abroad, professing one thing, but

underneath another, began buying up land and stirring up the

people.… The strangers, once thought terror's victims, became

terror's fierce practitioners." The poem concludes with

a comment on the Israeli-Jordan water politics of the 1960s involving

the use of the Jordan River. "But even now, to protect their

gains ill-got, as if the land was theirs and had the right, they're

threatening to disturb the Jordan's course and make the desert

bloom with warriors."102

The first complaint was sent to Robert

Moses by the officials of the American-Israel World's Fair Corporation,

the signatures including Harold S. Caplin, Chairman of the Board

and Zechariahu Sitchin, President. The officials called the mural

"propaganda against Israel and its people" and said

that "use of the fairgrounds for the dissemination of such

propaganda runs counter to the spirit of the fair as expressed

in its theme." On the other hand, King Hussein of Jordan,

who had visited the Fair on April 23, stated that he did not

find the mural offensive. "All pavilions are propaganda,"

he said. "We are not against the Jews, but we are against

Israel and the foreigners who took our homes and property."103

Article 16 of the Fair's by-laws stated

that "the Fair Corporation will not permit the operation

of a concession or exhibit which reflects discredit upon any

nation or state." Article 27 gave the Fair Corporation "the

right to censor all projects at the Fair site." By this

token, the American-Israel Pavilion had a right to request that

the Fair order the removal of the mural.104 Yet the response from the World's Fair was

not what they had hoped for. In a telegram from Robert Moses

the following day, it was clear that the Fair would rather not

be involved in the dispute. "The Fair cannot censor the

mural you refer to, even though it is political in nature and

subject to misinterpretation. We believe no good purpose would

be served by exaggerating the significance of this reference

to national aims or attributing racial animus to it."105

As the situation was publicized through

the press and individuals and organizations began to take notice,

the complaints of the public were redirected to City Hall. In

response, Paul O'Dwyer, Manhattan Councilman-at-Large, sent a

telegram to the Fair citing New York City's interest in the Fair

as a major investor, and his concern that the Fair "should

be used as a medium of propaganda by a nation dedicated to a

policy of extermination and genocide." "One must question,"

O'Dwyer wrote, "the propriety in the first instance of permitting

the use of city property to any nation whose avowed purpose is

to wipe its neighbor off the face of the earth." O'Dwyer

asserted that the mural in the Jordanian pavilion was "offensive

to our city and its people" and the permission for it to

remain made Peace Through Understanding a "meaningless

slogan."106 O'Dwyer,

along with another Councilman, filed a complaint with Mayor Wagner

as well.

On May 7, Joseph F. Ruggieri, Brooklyn

Councilman-at-Large proposed a law that would forbid the display

of any public item that "portrays depravity, criminality,

unchastity or lack of virtue of a class of persons of any race,

color, creed or religion" and called on Mayor Wagner and

Robert Moses to have the mural removed.

Jordan Pavilion officials indicated that

they threatened to close the pavilion if any

order to remove the mural occurred. Hashem Dabbas, a Jordanian

Pavilion administrator, reasoned that Jordan's interest in participating

in the Fair was to "show the American people what our problems

are."107

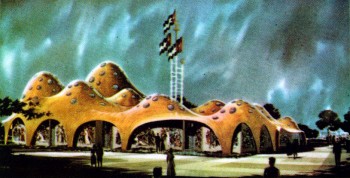

An architectural rendering of the

Pavilion of Jordan shows a one-story structure with a concrete

roof covered with gold mosaic.*

|

The Council's resolution gave some hope

to the officials of the American-Israel Pavilion, but with no

deadline for the mural's removal in sight and mounting protests

by visitors to the Fair and American-Jewish organizations, the

American Jewish Congress (AJC) asked the Fair for permission

to picket in front of Jordan's pavilion on May 25, which would

be the Fair's celebratory "Jordan Day" marking that

nation's independence. Robert Moses refused the AJC's request

succinctly. "We shall not license picketing to encourage

international incidents in a fair primarily devoted to promoting

friendship through increased understanding."108 In a statement to the press, Dr. Joachim

Prinz, the President of the AJC, rejected Moses's ruling. "Mr.

Moses' statement indicates that he regards himself as the sole

judge of whether picketing promotes or hampers international

friendship. In this country, no public official - even one so

eminent as Mr. Moses - has the authority to make such decisions."109 The Committee on American-Arab Relations

(CAAR) might have agreed with Prinz, because the day after Moses's

statement, Dr. Mohammed Mehdi, Secretary General of CAAR telegrammed

Moses asking for permission to picket the American-Israel Pavilion

on May 25 in retaliation to the AJC's request.

We beg permission to picket American-Israeli

Pavilion on May 25th. The existence of this anomalous pavilion,

which is neither American nor Israeli, is both propaganda and

an insult to the Arabs and the Americans. We would not have raised

the issue except for Zionist totalitarianism which is as intolerant

as fascism or communism. Full of hatred against the Arabs, the

Israeli-Americans behaved as if they were in Israel and not in

the midst of an open society. We resent Zionist endeavors to

remove [the] Jordan mural. Freedom of expression must be protected

despite Zionist intolerance.

Moses replied to Dr. Mehdi immediately.

"Let me urge you to drop the matter," he said. "Let's

work for friendship and peace."110

Dr. Prinz did not drop the matter, however,

and on May 25, he and twelve national officers of the AJC defied

the ban on unauthorized demonstrations that the Fair had put

into place because of threatened protests on opening day by civil

rights groups. They were promptly arrested by the Fair's Pinkerton

police force. The offenders were charged with disorderly conduct.

Dr. Mehdi publicly stated that "the fair regulation against

picketing is probably unconstitutional," but he did not

defy the ban. Instead his group demonstrated outside the New

York offices of the AJC and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL),

an organization which had filed a lawsuit in the State Supreme

Court earlier in the week requesting the closing of Jordan's

pavilion. 111

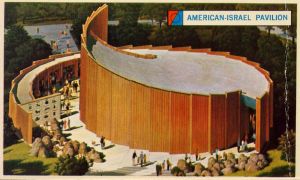

Architectural rendering of the American-Israel

Pavilion, a 45-foot spiral with a facade of African redwood mahogany.*

|

(left) Curving steel framework of the Jordan

Pavilion under construction. (right) The American-Israel pavilion

rises from Flushing Meadows in early spring of 1964.*

|

|

Testimony on the ADL's lawsuit began in

early June. For the first time, the World's Fair gave an argument

to back up their position on the mural. Bernard L. Sanoff, lawyer

for the Fair, said that the censorship clause in the Fair by-laws

was "obviously aimed at lewd and lascivious shows."112 The Fair indeed had been censoring some

of the entertainment shows that were not up to quality standards

dictated by Moses or were marked by any possible sexual explicitness.

Moses never denied that he felt censorship necessary for his

good, clean fair. In his opening day essay in the New York

Times, Moses explained the Fair's stance: "Can we survive

without a certain amount of over-the-line vulgarity just short

of censorship and police intervention? We have chosen the side

of the angels."113

Censorship of various pavilions was plentiful

throughout the length of the Fair. On May 9, Charles Poletti

ordered the closing of the French Pavilion because it was "not

French enough," according to the New York Times.114 Before the Fair opened, Moses asked the

Protestant and Orthodox Center not to show its short film "Parable,"

which depicted Jesus in a pantomime's makeup, because he felt

some fairgoers might find it objectionable. The film stayed and

was so popular that it helped in a substantial way to finance

the pavilion.115 A small-budget

rock show called "Summer Time Revue" was also ordered

closed by the Fair in August because Moses thought it was not

in "good taste." In justifying his decision, he said,

"Do you think that we want the church organizations to complain?

The Catholics for example? We invited them here." The producer

maintained that the show had not changed since Moses previewed

it himself, months before.116

Accordingly, the Fair decided censorship was appropriate when

a pavilion did not represent a country properly, when it showed

an exhibit that might offend visitors (especially of the religious

nature), or when it was tasteless. But when censorship was actually

requested for an exhibit that did not represent a country properly,

that did offend many visitors (especially religious ones - thousands

of protest letters were received by the Fair from Jews and Jewish

organizations), and about which many guests and public officials

would argue was tasteless, the Fair did nothing to cease the

complaints.

For Moses to have such strong concerns

about possibly offending the Catholics, it is

surprising that the Fair did not take into any consideration

how offensive the mural was to many Jewish groups and individuals.

According to Robert Caro, Robert Moses's biographer, "Every

one of the major religions in America was represented at the

Fair, save one, and Jewish leaders were increasingly perturbed

by the absence of any representation of their faith (some of

them seeming to feel that the Fair was not especially anxious

to have any)…"117

At the World's Fair there were eight official religious pavilions,

including the Vatican. Five of the religious pavilions, which

were provided rent-free, were placed in the International Area

of the Fair, and thus were under the care of the [Fair's International

Affairs and Exhibits (IAE) division], a staff that consisted

of not one Jew. Moses himself was born to a Jewish family, but

had repeatedly publicly renounced his faith.118 However, Moses's position against the Jewish

and Israel-supporting community at the Fair seemed to be something

other than self-deprecation or anti-Semitism.

The Jewish People did have representation

at the Fair with the American-Israel Pavilion, its major investors

prominent American Jewish organizations such as Hadassah and

the Zionist Organization of America. Originally, the American

Jewish community did plan to erect its own pavilion at the Fair,

with plans spearheaded by the Synagogue Council of America. But

in April 1963, the Council announced it would not be participating

for "practical reasons" that it did not elaborate upon.119 Meanwhile, Israel planned its own pavilion

and had made headway on the design of the building, but the Israeli

Cabinet pulled out of the Fair in October 1962 citing the high

costs of the land lease. Poletti admitted it was a "complete

surprise" and Moses "attacked" Israel's Prime

Minister David Ben Gurion for the withdrawal.120 Moses did not take kindly to nations withdrawing

from his Fair. For example, he was so outraged that Canada was

not participating, that he actually sabotaged the Argentina Pavilion

when he found out its major investor was a Canadian company.

Bruce Nicholson, a member of the IAE division remembers, "It

all seemed like a huge global game, pitting country against country.

We were our own State Department, Defense Department and war

strategists. And if it were necessary to sacrifice Argentina

to spite Canada, so be it."121

Architectural model of the winning design for

the official Israeli Pavilion at

the New York World's Fair. After the Israeli Cabinet rescinded

Israel's official participation in the Fair in 1962, the design

became the basis for their Pavilion at expo67 in Montreal, Canada.

Had the pavilion been built in New York, it would have occupied

the site where the African Pavilion stood.*

|

Israel was no exception to the wrath of

Moses's personal foreign policy. Despite the success of the quick

mounting of the American-Israel Pavilion, Moses's grudge towards

Israeli and Jewish groups lasted throughout the course of the

Fair.

Besides the mural controversy, there was

one other religious incident at the Fair that outraged local

Jews. In June 1964, a group of 80 students from the Bellerose

Jewish Center visited the Fair's Hall of Education. At this Hall

was an exhibit by the American Board of Missions to the Jews,

Inc., which was established in the 19th Century to "promulgate

the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ among the Jews." The

Mission designed its exhibit with the word "Israel"

across the top. On that day, the Baptist minister who ran the

exhibit discreetly lured a 12-year-old boy away from the group

and brought him to the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association

Pavilion to watch the revivalist's film. When the boy's rabbi

and mother made the accusation that this minister attempted to

convert the young boy, the Fair promised to inspect the situation

and if all were true, the exhibit would be closed. However, no

action against the American Board of Missions to the Jews was

ever taken. The Reporter criticized the peddling of religion

at the Fair. "In the midst of the fevered huckstering at

the 1964 New York World's Fair, religion has returned…competing

hard with the other exhibitors in selling a unique product."122 "It is difficult to tell where the

fair begins and religion leaves off," goes an article about

opening day in the New York Times.123 Religion was a prominent exhibit at the

Fair. But now it looked like Moses had religious war on his hands.

On the morning of June 7, when the Commissioner

General of the Jordan Pavilion, Ghaleb Barakat, arrived at work,

he noticed that the Jordanian flag flying atop the pavilion had

been replaced by a blue and white flag reading "American

Israel." The culprit, if found, was never made public, but

the incident prompted Abdul Monem Rifa'I, Ambassador of Jordan

to the UN to write to Francis Plimpton, Deputy Permanent Representative

of the US Mission to the UN in order to "bring the case

to the appropriate authorities." According to Rifa'I, besides

the "hostile activities" of the mural protesters, several

other incidents had occurred, including anonymous bomb threats.

His letter clearly indicts "a certain group of citizens

in New York," the American Jews, as the guilty parties in

the recent occurrences, and with his letter brought the controversy

over the mural into the international realm.124

On June 23 City Council released its resolution

calling for the removal of the mural, "which acts as a daily

and constant irritant and as a source of insult to millions of

people in this City, State, Country and around the world."125 A week prior to this announcement, Dr. Mehdi

met for an hour with the General Welfare Committee (which included

six Jewish members) and said that Jews were offended by the mural

"because of a sense of guilt."126 Dr. Mehdi's visit to Council seemingly caused

more harm than good for his cause, and the adoption of the resolution

passed unanimously.

Adding insult to injury, the American-Israel

Pavilion unveiled a parody to the mural on their site. It included

a blown-up picture of the mural, along with a new poem written

by Chairman Caplin, entitled "Peace Through Understanding".

Part of it reads: "We hail our neighbors here at this fair.

We degrade them not and ask the same in return. And to one and

all, pledge our hope for 'peace through understanding.'"127 The American-Israel Pavilion's new poem

did not cause much of a stir, but Moses sent Lionel Harris, a

member of the IAE who was assigned to the Jordan Pavilion, into

the pavilion to inspect it for offensive items against Jordan.

Harris reported that the entire pavilion was done in good taste

and without hostility.128

The Fair Corporation President was under

a lot of pressure by the June 22 Board of Directors meeting,

as a division began to arise between the Board and Moses over

the issue of the mural. Several members of the Board were hoping

to discuss the controversy at this meeting, although the issue

was deliberately left off the agenda. Congressman Seymour Halpern,

a Board member, thought the issue deserved Board attention, and

submitted a formal request for convoking a special meeting in

early June. In his letter to Robert Moses, Congressman Halpern

wrote:

I do not think that New York

State would have incorporated the Fair nor New York City leased

the site had it been known that this sort of display would be

tolerated. I do not think that the people of New York would have

consented to have the Fair in their midst if they were aware

that it would become a vehicle not for encouraging global harmony

but for perpetuating international conflict.

He cited a by-law stating that when a director

is joined by four fellow members of the Board, they may call

a meeting to act on a matter of importance. Moses got back at

the Congressman, though. "Incidentally you are in error

as to the number of directors who can call a meeting on their

own motion," wrote Moses. "A recent amendment to the

By-Laws requires 50 directors to initiate such a meeting."129

A very prominent member of the Board of

Directors, New York Senator Kenneth B. Keating spoke at the dedication

of the American-Israel Pavilion on "American Israeli Day"

at the Fair, May 24, against Moses's will. In a letter to Keating's

office, Moses said of the upcoming speech, "I strongly urge

him not to rock the boat."130

At the dedication, Keating did not mention the Jordan Pavilion

specifically, but spoke highly of the American-Israel Pavilion

as one that "contrasts strongly with those who seek to hide

the truth and obscure the realities of the Middle East."131

House of Representatives Chairman of the

Committee on the Judiciary, Emanuel Celler was one of the first

Directors to seek answers from Moses. In a letter from May, Congressman

Celler wrote, "Were I to draw an analogy of a Soviet Union

Pavilion on our fairgrounds bearing a message addressed to the

Western World, 'We will bury you,' would you not agree that such

statement of hostility would be out of place?...Even in the mildest

of terms, such murals are, we must concede, offensive to the

canons of good taste…" [Empahsis added]

State Senator Joseph Zaretzki, the minority

leader, drafted a resolution to force the Jordan Pavilion to

remove the inscription from the mural, which he tried to get

on the Board agenda for June 22. Moses wouldn't allow it. At

the meeting, the opposition to Moses came to a head. Liberal

Party Vice-Chairman Alex Rose, who authored his own resolution

urging the Fair to change its neutrality policy on the mural

issue, was "gaveled down" by Moses when he tried to

introduce his resolution. Moses ruled that due to the pending

litigation in the courts by the ADL, the Board was in no position

to discuss the matter. The Board erupted into shouts and gavel-pounding,

and Senator Javits asked for a vote on the whether the debate

should be closed or not. When Moses got his way 59 to 24, Senator

Zaretzki brought up his resolution again. Moses ignored Senator

Zaretzki, and began talking over him with other business until

finally Zaretzki relented.132

The next day, Alex Rose publicly announced

his resignation from the board. He argued that the mural was

"sheer war propaganda" being presented to "unsuspecting

viewers." "Little do they know," the letter said,

"that instead of peace through understanding they are getting

war through misunderstanding."133 Then Senator Zaretzki, in a television interview,

called Moses a "despot", referred to him as "Boss

Moses" and labeled the Board of Directors a "useless

body."134

The Fair never officially commented on

the Board proceedings and the resignation of Alex Rose, nor did

it enforce the City Council resolution to remove the mural. The

Fair issued a statement against the resolution, arguing that

the Council was asking for the "suppression of free speech."

The statement went on to say that the Fair has "no power"

to order the removal of the mural.

Moses's arguments, however, were losing

footing with all of the negative publicity about the Board of

Directors meeting, the City Council resolution, and the lawsuits

pending in State Supreme Court. On July 9, Moses gained a small

victory when Justice George Postel dismissed the lawsuits against

the Fair. His decision was based on the technicalities of the

lease between the Fair Corporation and the City of New York,

which did not give any rights to the city for the regulation

of exhibits. This ruling nullified the City Council resolution.

Additionally, according to the New York Times, Justice

Postel also "rejected the fair's contention that a constitutional

issue of censorship of a political message was involved."

The judge admittedly sympathized with the plaintiffs, and regretted

that "those in a position to cure or alleviate the sore

are unable or unwilling to do so." Moses, triumphant, approved

of the decision, which "fully upholds the position we have

taken, which was based on principle."135 Just what principle that was, Moses never

made clear.

Hostile Neighbors:

The curving roof line of the Jordan pavilion (center) can clearly

be seen in this view of the Fairgrounds from the Skyride . In

the near-distance, behind the Jordan pavilion, can be seen the

mahogany spiral with yellow roof of the American-Israel Pavilion.*

|

Robert Moses had another reason to be happy

during July of 1964. It was then that he,

Charles Poletti, and Lionel Harris were notified that they would

be receiving the Al-Kokab, the Star of Jordan, First Class. The

award they were to receive was the highest honor that the King

of Jordan could bestow upon anyone. Harris reported to Poletti

that the Jordan Consul in Washington "stressed the fact

that…while the Jordanians are deeply grateful for our stand

in the matter of the mural and for all our help in general, he

wants us to understand that the award is an overall token of

esteem, and is not directly tied to the mural controversy."136 But Moses reflected several years later

in an article, that "Jordan and Arab states were so astonished

by the nonpolitical conduct of the fair heads," that he

and the others received that award "for our contribution

to understanding and friendship of nations at the World's Fair."137

These Fair administrators had a long and

comfortable relationship with Jordan and its

King since early Fair planning stages. Jordan was the first Arab

state to accept the Fair's invitation, on March 2, 1961. Moses

visited Amman with a Fair delegation, and King Hussein likewise

visited the Fair once before it opened, and also on April 23,

1964 when a luncheon in his honor was held at the Terrace Club

at the Fair. (No head of Israel ever visited the Fair, though

Levi Eshkol, Prime Minister canceled a scheduled visit for June

11 in protest of the mural.) 138

Moses had taken a particular interest in

Jordan because of his experience as an urban planner. He had

theories about water conservation, energy opportunities on the

Jordan River, housing for refugees, and city development. Moses

felt that his experience as a planner in New York City was enough

for him to make judgments on the economic and political situation

in Jordan, and with the start of his relationship with King Hussein,

he really began to indulge in his theories. Long after the Fair,

Moses continued coming up with plans for Jordan and tried to

put together a committee to study development opportunities there.

In 1971, Moses wrote an op-ed for the New York Times entitled

"Harness the Jordan." In this piece, Moses urged the

United States to take interest in Jordan for "multipurpose,

regional power and reclamation and pave the way for industrial

progress." (Moses discussed the mural controversy in this

editorial by claiming that "fanatics" brought the case

to court "to stir up trouble within the fair, in the city

administration, among political leaders sensitive to racial and

religious issues and among professional religionists.")

In a 1977 letter Moses wrote to WNET Channel 13 in hopes of receiving

its support for a committee on Jordan, he said

This problem is for engineers,

not diplomats and politicians…With my Fair and engineering

associates I became interested in a scientific engineering of

the Jordan, Jordan River, Israel and the PLO dispute. It occurred

to some of us that the King of Jordan might take the PLO into

Jordan as a state within his nation based on sound, constructive

engineering principals.

While Moses never got a committee of his

sort to come about, it seemed that the Fair inspired him to think

internationally about his once local positions. After the Fair,

Moses went on to consult on urban planning issues all over the

world.139

Moses's biographer, Robert Caro, had a

different opinion about Moses's expansion of

scope. His poor relations with Israel after their official pavilion

withdrew hurt Moses's Public image in the world outside New York.

"The Fair destroyed Moses' reputation…because he had

to have his own way about everything, even in a field in which

he was the newest of newcomers. He could have his own way in

New York, but in putting on a World's Fair, he had to deal with

other states and countries - and his arrogance antagonized them."140 Caro is not entirely correct regarding Moses

and Israel. The mural issue was subdued in the Israeli press,

and the major papers Ha'Aretz and Ha'Doar actually

stressed that the complaints over the mural were giving the Jordan

Pavilion extra publicity. Nearly all of the chastising towards

Moses came from the local Yiddish Press and from American Jewish

organizations.

But it was the antagonism of the people

in his own country and city that gave Moses immediate concerns

to deal with. The NAACP and CORE sued the fair for the right

to hold protests, since many of their members had been arrested

at the start of the Fair for organized "stall-ins"

that were staged to attract attention to the Civil Rights movement

in the US. Between Civil Rights protesters and mural protesters,

the Queens Criminal Court had 200 cases by mid-June 1964. Judge

Harold R. Tyler of the Federal Court ruled on July 1 that Fair

protesters did have the right to distribute handbills, although

not to picket in a way that would block roadways or paths. Since

the twelve AJC picketers did not cause a disturbance in May,

Judge Dubin of the Queens Criminal Court acquitted them all on

July 29. In addition, he stressed that their right to picket

in a public space was guaranteed under the First Amendment, since

in 1963 the Legislature ruled that the Fair, a private corporation,

was to be considered public property. Judge Dubin's ruling was

a victory for the AJC, which was countersuing the Fair for the

right to picket under the First Amendment. That suit was finally

settled in April of 1965 in the State Supreme Court, just in

time for the start of the 1965 season. The Fair agreed that the

AJC could assign two members to distribute handbills from designated

spots outside the Jordan Pavilion, a concession that the Fair

could have easily made a year before to avoid the drama that

instead took place.141

Sympathizers with the Jordan Pavilion were

not pleased with the course of events. Dr. Mehdi again wrote

to Moses asking for permission for CAAR members to picket the

American-Israel Pavilion, as well as "the two people distributing

leaflets" at the Jordan Pavilion. Before receiving this

permission, CAAR sent two members to hand out leaflets in front

of the American-Israel Pavilion which said "Don't buy Israel

bonds, buy U.S. bonds." On April 30, some of the entertainers

from the American-Israel Pavilion began to taunt them, and a

fistfight broke out. Zechariahu Sitchin, President of the American-Israel

Pavilion, expressed his disappointment that the fairgrounds should

be turned into a "battleground."142

Workers at the American-Israel Pavilion

continued to provoke the CAAR picketers, when on May 1 they arranged

a lunch table for them near the entrance to the pavilion. "On

the table were six bologna sandwiches and four bottles of Israeli

beer," reported the New York Times. "Also on

the table was a large sign saying: 'For your misguided pickets

- kosher food, compliments of the American-Israel Pavilion.'"

-

The invitation to participate

in the World's Fair was presented to the Prime Minister of Israel

in January, 1961, by the World's Fair delegation to the Near

East. Israel selected a site facing the main mall of the Fair.

-

(from left to right) Governor Charles

Poletti; His Excellency David Ben Gurion, Premier of Israel;

Dr. K. C. Li

-

-

Israel withdrew their official

participation in the Fair in 1962.*

|

Beyond those few incidents, picketing,

and the controversy itself, surprisingly seemed

to fade from protesters' and the public's mind during the 1965

Fair season. Like nothing ever happened, the mural with its inscription

remained. The only apparent effect of the controversial events

was the slight deterrent of American Jews and Jewish organizations

to attend the Fair. Some Rabbis opted to persuade their congregants

to boycott the Fair, although the number of Jews who actually

boycotted is unknown and thought to be rather slim. On the issue

of censorship at the Fair, the situation also had little effect.

The Fair continued to censor objectionable exhibits during and

after the mural controversy. The only thing ever removed from

the Jordan Pavilion, though, was an "unauthorized vending

machine" in 1965.143

© Copyright 2005 Sharyn Elise Jackson, All Rights

Reserved.

|