|

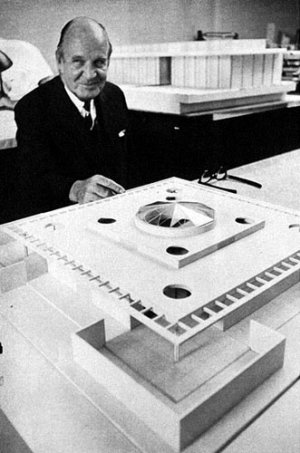

Architect Edward Durell Stone, whose U.S. pavilion was the

hit of the 1958 Brussels World's Fair, has every reason to be

confidently relaxed about the home he has designed for this World's

Fair. Sharing a landscaped site with a traditional and a contemporary

house in The House of Good Taste exhibit, it will be visited

by more people than any other all-out modern home in history

and may well be the most influential, thought-provoking home

ever built. Shown above is the scale model.

Those who prefer a traditional house might dismiss this one

as too modern. Those who prefer modern design might quickly label

it as too conservative and formal. Both judgments would be hasty.

For, paradoxically, Stone's trend-setter offers a striking answer

to America's most modern problem - the density dilemma - in a

traditional way that dates back to ancient Mediterranean cultures.

The World's Fair House is a three-dimensional dramatization

of Stone's deeply felt convictions about how people will live.

As he explains it: "If the colonies had been settled by

the French or Spanish, we would have fallen heir to a completely

different tradition. The ancient Pompeians, for example, built

their houses wall to wall, presenting a solid front to the street.

Behind this stretched a beautiful atrium (a lighted room) and

an open courtyard with all the rooms grouped around it."

Adapting this idea, Stone created a house that looks inward and

develops its personality from the character of the individual

family. Walls enclose virtually all of the site. Windows look

out on the cloistered gardens that serve as buffer zones between

street and neighbors.

However, our housing traditions are Anglo-Saxon. Our Colonial

ancestors sought to live in the manner of the English country

squire - a freestanding house on a private plot of land. "As

a result," says Stone, "the suburbs of our cities are

today being used up by little boxes set on handkerchief lawns

... which is the most impractical way in the world to build dwellings.

I think we should stop kidding ourselves and recognize that our

land is very precious. We had better cloister our houses and

be less wasteful of it. By building wall to wall, with enclosed

courtyards, we also gain that other precious commodity so essential

to peace and tranquility - privacy."

| (Above) This view of Fair house

model in Stone's New York City drafting room shows square roof

with latticed overhang, central glass dome. Walls to property

lines enclose open courtyards off each corner bedroom. |

|

|

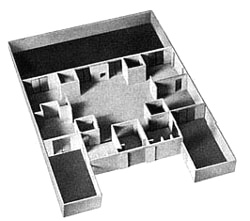

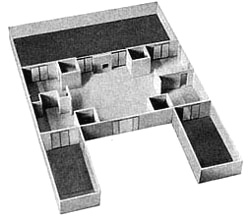

| (Right) These three compact plans

show how the Fair house can be built wall to wall in space-saving

cluster communities without loss of privacy. Center version uses

atrium as living room; bottom, without dining room, is three

bedroom plan. |

|

|

|

|

A Home with Three Plans for

Privacy

Edward Durell Stone's World's Fair House is significant for

two reasons: He tackles the fundamental problem posed by our

soaring population - the need to live closer together. His solution

is a house of beautiful simplicity and style. It centers around

a spacious atrium, a 1,026-square-foot room with a 22-foot faceted

glass dome. (The all-out World's Fair version will include a

6-foot circular reflecting pool.) This is the heart of the home

and the key to Stone's design. All other rooms are planned around

the central core, as shown in illustrations at right. These give

you a clue to the house's versatility, but none to its warmth

and livability.

The real house at the Fair will feature many innovations,

from rugged new white wall paneling on the exterior to oil-finished

teak panels on the interior. It will be handsomely furnished

by decorator Sarah Hunter Kelly, from fine art to a fine kitchen;

landscaped for minimum maintenance by Clarke & Rapuano, with

flowering trees and rose gardens off each bedroom.

Not everyone will find this his "perfect" house.

But all will agree that Stone has designed something exciting

to see and challenging to think about. After all, that's why

we have World's Fairs.

|