|

I WAS HIRED in November, 1960 by Walter Dorwin Teague Associates, an industrial design firm, with the promise to be the architect of record with full authority in the design of a new building for Gas Inc. This building was to be part of the New York World's Fair of 1964-65. This was my first large commission as a registered architect. I was thirty-four and it was exciting.

As the New Year of 1961 began, I was chafing at the bit to start designing the Gas Pavilion, as we were now calling the building. I had no "program," which is the list of parameters and requirements that one must have in order to start designing. Also, to design a building one must visit the site to drink in the environment in which the as yet unborn building would be set. This would not be hard for the site was in Flushing and I lived in Flushing.

I did get a chance to sit down with Dorwin Teague and discuss his thoughts on what the building would have to encompass. He had been captivated with remembrances of the past. He remembered how thrilled he had been as a child traveling on an excursion on the Hudson River Line and being able to see so much of the moving parts of the ship. It was set so that the traveling public could see the mates at work and watch the moving parts. It was much like an exhibit. He felt that the exhibits within this new building should be out in the open and visible to all.

Another memory for him from earlier days was the very successful exhibit at the last Fair in 1939, the General Motors Exhibit. But he felt that in part the success created a drawback (i.e. the enormous crowds). The crowds were brought on by the attractiveness of the show. Everyone wanted to see the "World of Tomorrow" and the lines were long. Dorwin felt that there should be some way to take the people into the pavilion and allow them to have an overall view of all the items in the exhibit and then to see what they found exciting. They then could leave as they wished. He felt that this could be accomplished with some sort of elevated turning ring that might be accessed by some kind of moving stair.

He also said that he had been talking with the Executives of Gas Inc. and they agreed with him that it would be good to have a fine restaurant as part of the building. These general concepts were enough for me to start envisioning this new building. I would later have to fine-tune the detailing but it was a small start for me.

It was very cold that January of 1961, and as I stood on the sidewalk in front of a store window on Madison Avenue, looking at a television set, watching the new President John Kennedy take the oath of office, I had a feeling of great promise ahead. Bob Blood, the Chief Exhibit Designer for our Pavilion, had still not gotten over the way Kennedy "stole" votes from Nixon. But whatever. Kennedy was now President. He seemed to symbolize what we were hoping for in the future months. In my mind this new building and new administration were linked.

On March 2nd I went to the Fair Grounds to see the site. It was very strange. This was the site that I had visited as a young boy in 1939 at that other famous Fair. I walked over the roads that were now in bad repair with cracks and ruts and small weeds growing through in parts. It was sad to see, remembering a past time; like looking at an ancient ruin. That moment of melancholy was soon displaced by the realization that now there would be a rebirth with new roads and new trees and bushes and there would be new sites for many new buildings. I walked, with my map of the site plan of the new Fair. I remembered as a twelve-year-old walking these very paths that were then alive with the color of trees and flowers and with excited people in light colored summer clothes. Now all was dead as I came to the site where my building would be. It was over two acres, fully open on three sides and flat. It was right near the main gate. It was exhilarating for the boy of eleven to return as the man of thirty-four; but now instead of being excited by the "buildings of the future," I would be one of those who conceived of and brought forth a building of the future.

There was another item that seemed to be in my almost subconscious mind. It was the tree. Back in July of 1959, Aleen, my wife, and I moved with our four very young children (Mary Ellen, Joseph, Susan and baby Maureen) into our newly purchased house in Flushing. It was in a state of poor repair and I had much work to do to fix it up. There was one thing about the setting that gave me some uplift. It was a solitary tree, probably an elm, that stood alone in the backyards of one of the adjoining properties. It seemed so vibrant and strong and indestructible. Then one day some men began to demolish the fine homes that were at our rear and other men came with large saws to cut down that great tree. I now remembered the big beautiful tree.

As I walked around the grounds where this new building was to be, I tried to get the feel of the site. I knew that Dorwin had hopes that we could have an open building and slowly the building began to take shape in my mind. The ground floor would be a stylized garden and the roof supports would emulate the inspirational tree in my back yard. It was not exactly clear but the site was more rectangular than square so the roof that these "trees" would hold up would be like the tops of two joined parasols. This indeed was the basic concept; two large white trees holding the roof. I would have to get back to the office and work the concept design out on paper.

It took two weeks for me to get the very basic idea of the large open garden with its two tree-like columns and parasol roof set on paper. But I knew where I was going and even if it would have to be modified as time went along, the basic idea was there. I could include Dorwin's ramps and ring and we could have a space on the west end of the plot for a fine restaurant.

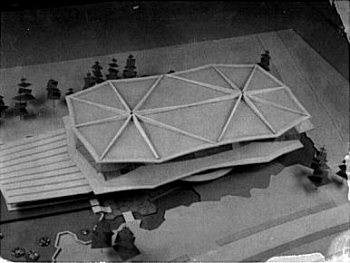

I made some preliminary drawings and on March 15th I had lunch with Percy Ifill, a colleague from my days at the LeMaire office. I told him, in general, how I saw the concept of the new building. He had a sensitive feel for all types of design and he thought it fine. He recalled my concept for the Roosevelt Memorial which had no walls at all, just a simple square roof held up by cables attached to pylons located far from the main building. My concept for the Gas Pavilion was different in that it was to be air-conditioned and would have to be enclosed and that would be the main problem. It would have to be open with easy access but parts of it might have to be enclosed in glass. The next day I started the real defined design. I made models of the building in paper and cardboard. I had the impulse to take Polaroid pictures of them and as a result this record remains. It is interesting, looking back after almost forty years, how amazingly similar those rudimentary models are to the building as it finally came to be.

|

Poloroid photograph of Mr. Mangan's cardboard model of the Gas Pavilion, March, 1961

|

I reviewed what I was doing with Dorwin and he was thrilled.

It had much of what he had asked for as far as employing the

moving ramps and the turning ring. It was easy for me to show

him how this accomplished what he had described. The people would

not have to wait in line and they would be scooped up on to these

escalators and on to the moving ring where they could look down

into the garden below and see which particular exhibit they might

go to after they exited the ramp.

Bob Blood proceeded to hire two helpful young designers, Bill Fisher and Art Clarke, to work on special design elements and he went about the job of searching for the firm that would run the restaurant for the duration of the fair. It was necessary that he and I work with the restaurant operator to set all the requirements for the restaurant and the kitchen and any special show kitchens if finally incorporated into the grand scheme. As it turned out, Restaurant Associates got the commission and under Joe Baum the Festival of Gas Restaurant was one of the finest at the Fair. |

Original Design Specifics

|

The ring (carousel) would set between the two tree-like columns. They, being close to 60 feet high, would provide the roof drainage along with support. The restaurant would be about 4,000 square feet with capacity for 250 to 300 patrons. The massive roof would be held up by only two columns and would cantilever in two directions. There would be a platform for a special club with about 2,300 square feet of usable space, also with only two columns. It would have dining facilities and could be used by the Gas Inc. people and their guests. Opposite and south of the Club would be another space on a platform to be for offices and for mechanical equipment

I knew the building would have to have glass walls in the club and restaurant but I came upon something new: air curtains. These were large entryways that made use of moving air to contain the air conditioning and still allow people to move in and out through them and the velocity of the air would not blow off a lady's hat. Why not extend them to cover areas greater than just a large door. This brought me to another element that was incorporated: the long side platforms that would connect the club at the north and the other office platform at the south. These platforms would hold powerful fans that would blow down walls of air. It was innovative.

|

Construction of the Gas Pavilion, July 30, 1963

|

|

Construction of the Gas Pavilion, December 31, 1963

|

|

It was sad for me later, but because of budget cutbacks the long

platforms with the fans for the air walls had to be abandoned

and the great sloped glass walls that contained the upper part

of the exhibit space also had to be abandoned. (Note, these features

were depicted in the $15,000 model - see section below).

We worked with our Landscape Architects - in particular with Tom Kane and Ken Stoner - on the marvelous water surround of the east side of the building. The water, constantly in motion, filled the whole area around the restaurant and then came over a little falls, into a stream and gathered then into the center of the main exhibit floor in a small pool. From there it was pumped back to start its circuit again. In this pool was a special sculpture by Jan Peter Stern, a young sculptor hired by Bob Blood. It was a very effective symbol of a gas flame done in bright stainless steel rising over eighteen feet. |

Completion of the Building

|

Dorwin and Bob worked hard on getting Air Research from Arizona to provide the gas turbines for the special electric installation with the multi cycle power for the lighting. There was a wonderful moment in early 1964, weeks before the Fair was to open, when power at the main switch failed and plunged the fair into darkness. Then, easily visible from all around the fair site, stood the great roof of the Gas Pavilion with its two big "trees" glowing alone in the dark night sky. It just happened that the turbines with their output of multi cycle electricity were being tested at that time, so the power was there for the building to be lighted up while the rest of the fair site was temporarily in darkness.

|

Work Nears Completion

|

|

March 31, 1964

|

|

| Enhancing the main body of water that surrounded the restaurant were a number of bright, white fiberglass hexagonally shaped "Lily Pods" filled with bright flowers of the season. They ranged in size from five to eight feet across and gave the impression of giant Lily pods floating on the water. |

Workmen install "hanging glass" walls

|

|

A marvelous clear view with no metal obstructions visible

|

|

| We had made connections with Otto Hahn of Glasbau Hahn in Frankfurt, Germany and set up the first installation of "hanging glass" in this country. This glass installation made up the outside walls of the restaurant and in the Private Club that was located directly above the restaurant. The glass lites ( pieces) were hung, much the way clothes hang on a clothes line but each lite ( piece) was held together with six inch wide clear glass stiffeners that were glued to the main pieces of glass. The effect was a marvelous clear view with no metal obstructions visible. It was very effective. |

The Lab and the $15,000 Model

|

It was expected that we would build a model that could be used to work out design problems and when finished be used for fund raising. It could be shipped around the country to various gatherings where the participants could see what their money was going to produce and be a vehicle for local press handouts. This model would be built in what was called the Lab or at times the Shop. The Lab was located in an industrial section of Manhattan on the second floor of a partially used building on 11th Avenue. It was quite large and was fully equipped with every tool available to build models of every sort.

$15,000 Model of the Gas Pavilion

|

|

In the lab the model makers would make something as small as a full tube of a new brand of toothpaste or as large as a partial interior fuselage of a new 707 jet. The Lab was under the direction of Dan Cardozo and he reported to Bob Ensign. Every project in the Teague office was in some way under the direct responsibility of one of the partners. Teague's being an Industrial Design Office needed such a tool and it was in constant use.

|

Ribbon Cutting Ceremony upon the opening of the Festival of Gas Pavilion. (pictured from left to right: Joseph Mangan, Architect; Dorwin Teague, Designer/Partner-in-Charge; William Hamilton, Vice President of Gas Inc.; Stanley Finch, Project Director,Gas Inc.)

|

|

Source: An original article by Joseph J. Mangane: © Copyright 2000, Joseph J. Mangan, All rights reserved

| In October of 1965 the Fair closed. It was all over. All buildings were to be removed after the Fair was over (this provision was in all leases) but the Federal and State buildings and the fair symbol, the Unisphere (a stainless Steel globe of the world) were allowed to stay. There was a move to try to keep the Gas Pavilion but after months of negotiation that was ended and in 1966 the Gas Pavilion was torn down and its remains sold for scrap. |

| Joseph J. Mangan was born in Pittston, PA, on November

23, 1926. He attended both the University of Scranton and Pennsylvania

State University and is a registered architect in five states.

His architectural office, formerly in New York City, is now located

in Ho-Ho-Kus, NJ, where he resides with his wife of 49 years,

Aleen. He is the father of six children and grandfather of ten. |

|