|

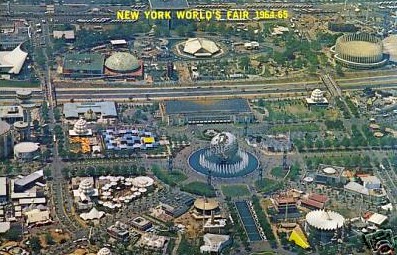

The 1964/1965

New York World's Fair was the second World's Fair to be held

at Flushing Meadows Park in the Borough of Queens, New York in

the 20th century. It opened on April 21, 1964 for two six-month

seasons concluding on October 21, 1965.

-

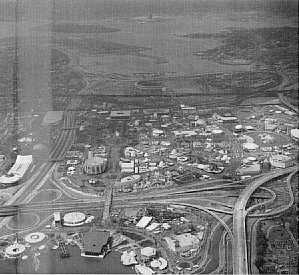

Postcard showing

an aerial view of the Fair looking west - presented courtesy

-

John Pender collection

|

It was the largest

World's Fair ever to be held in the United States occupying nearly

a square mile of land. Truly a "Universal and International"

class exposition, it was not sanctioned by the Bureau of International

Expositions (BIE) and is often overlooked by historians because

it was not an "official" World's Fair. This lack of

BIE endorsement meant that many large European nations including

Great Britain, France and Germany, as well as Canada and Australia,

chose not to participate in the Fair. Most international exhibits

were sponsored by tourism and industrial concerns and not officially

sanctioned by their governments.

More important

to this exposition than international participation was extensive

involvement of United States corporations as exhibitors. American

industry spent millions of dollars to create elaborate, crowd-pleasing

exhibits. Critics of the Fair charged that the heavy influence

of industry created an overly commercial atmosphere.

The Fair's theme

was "Peace Through Understanding," dedicated to "Man's

Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe"

and was often referred to as an "Olympics of Progress."

The theme center was a 12-story high, stainless-steel model of

the earth called Unisphere with the orbit tracks of three satellites

encircling the giant globe.

By the time the

gates closed more than 51 million people had attended the exposition;

a respectable attendance for a World's Fair but some 20% below

the projected attendance of 70 million. The exposition ended

with huge financial losses and amid allegations of gross mismanagement.

Today the 1964/1965

New York World's Fair is remembered as a cultural highlight of

mid-twentieth century America. It represents an era best known

as "The Space Age" when mankind took its first steps

toward space exploration and it seemed that technology would

provide the answers to all of the world's problems. The exhibits

at the Fair echoed a blind sense of optimism in the future that

was prevalent in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Its architecture

can be described as "Populux" or "Googie" where

flying saucer shapes, vast cantilevers and towering forms make

up the majority of pavilion design.

Controversial

Beginnings

The Fair was

conceived by a group of New York businessmen who fondly remembered

their childhood experiences at the 1939/1940 New York World's

Fair and wanted to provide that same experience for their children

and grandchildren. Thoughts of an economic boom to the city as

the result of increased tourism was also a major reason for holding

another fair a scant 25 years after the 1939/1940 extravaganza.

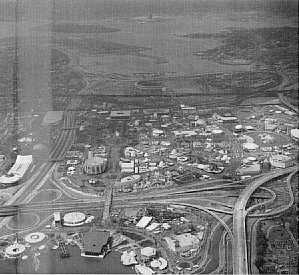

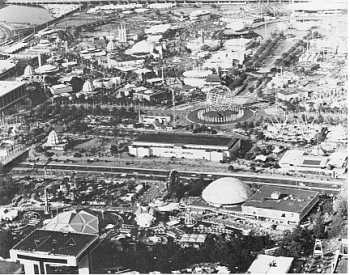

The Fair looking north toward

LaGuardia Airport and Shea Stadium

|

World's Fairs

in the United States are not government financed. Organizers

must turn to private financing and the sale of bonds to pay the

huge costs to stage them. The organizers turned to New York's

"Master Builder," Robert Moses, to head the corporation

established to run the Fair because he was experienced in raising

money for vast projects. Moses had been a formidable figure in

the city since coming to power in the 1930s. He was responsible

for the construction of much of the city's highway infrastructure

and, as Parks Commissioner for decades, the creation of much

of the city's park system.

In the mid-1930s

he oversaw the conversion of a vast Queens garbage dump into

the glittering fairgrounds that hosted the 1939/1940 World's

Fair. Called Flushing Meadows Park, it was Moses' grandest park

scheme. He envisioned this vast park, comprising some 1300 acres

of land and located in the geographical center of the city, as

a major recreational playground for New Yorkers. When the 1939/1940

World's Fair ended in financial failure, Moses did not have the

available funds to complete work on his project. He saw the 1964/1965

Fair as just the vehicle he needed to complete Flushing Meadows Park.

Moses realized

that in order to ensure profits for the Park, the Fair Corporation

would have to maximize receipts from the Fair. The Fair would

need an attendance of 70 million people in order to turn a profit.

This lead to the first of two decisions which would cause the

Fair to come to blows with the Bureau of International Expositions,

the international body headquartered in Paris that sanctions

World's Fairs. The Corporation determined that attendance that

large would mean the Fair would have to run for two years. BIE

rules state that an exposition may only run for one, six-month

period. Secondly, the Corporation decided to charge rent to exhibitors.

This was also a direct violation of BIE rules which state that

no host may charge exhibitors rentals. In addition, Montreal,

Canada, had been selected to host the Universal and International

Exposition of 1967 (Expo67) and BIE rules stated that only one

Universal exposition may be held within a 10-year time span.

Moses was undaunted

by the BIE's rules when he journeyed to Paris to seek official

approval for the New York Fair. When the BIE balked at New York's

application, Moses, used to having his way in New York, angered

the members of the BIE by taking his case to the press publicly

stating his disdain for their organization and their rules. The

BIE retaliated by taking the action of formally requesting their

member nations not to participate in the New York Fair. The 1964/1965

New York World's Fair became the only significant World's Fair

in history to be held without BIE endorsement.

International

Participation

Major foreign

exhibits were absent from the Fair due to the BIE decision. New

York in the middle of the twentieth century was at a zenith of

economic power and world prestige. Unconcerned by BIE rules,

smaller nations saw it as an honor to host an exhibit at this

Fair in the world's most prestigious city. Therefore most international

representation came from smaller nations and so called third-world

countries. The absence of Canada, Australia, major European nations

and the Soviet Union tarnished the image of the Fair. In

the end, only Spain and Vatican City hosted a major national

presence at the Fair. Other international participants included

Japan, Mexico, Sweden, Austria, Denmark, Thailand, Philippines,

Greece and Pakistan, to name a few.

The Fair looking east with

Unisphere near the center of the photograph

|

One of the Fair's

most popular exhibits was the Vatican pavilion where Michelangelo's

sculpture Pieta was displayed. A recreation of a medieval Belgian

Village proved to be very popular also. There, Fairgoers were

treated to a new taste sensation in the form of the "Belgian

Waffle" -- a combination of waffle, strawberries and whipped

cream. Elsewhere, emerging African nations displayed their wares

in the Africa Pavilion. Controversy broke out when the Jordanian

pavilion displayed a mural emphasizing the plight of the Palestinian

people. The city of Berlin, a Cold War hotspot, hosted a popular

display.

American

Industry Takes the Spotlight

At the 1939/1940

World's Fair, industrial exhibitors played a major role by hosting

huge, elaborate exhibits. Many of them returned to the 1964/1965

Fair with even more elaborate versions of the shows they presented

25 years earlier. The most notable of these was General Motors

whose Futurama, a show in which visitors seated in 3-abreast

moving armchairs glided past detailed miniature dioramas showing

what life might be like in the "near-future," proved

to be the Fair's most popular exhibit. Nearly 26 million people

took the journey into the future during the Fair's two-year run.

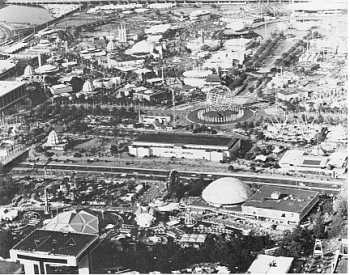

The Fair looking west with

the Industrial Area in the foreground

|

Other popular

exhibits included that of the IBM Corporation where a giant 500-seat

grandstand was pushed by hydraulic rams high up into an ovoid-shaped

rooftop theater. There, a 9-screen film showed the workings of

computer logic. The Bell System hosted a 15-minute ride in moving

armchairs depicting the history of communications in dioramas

and film. DuPont presented a musical review by composer Michael

Brown called "The Wonderful World of Chemistry." At

Parker Pen, a computer would make a match to a world-wide pen-pal.

The surprise

hit of the Fair was a non-commercial movie short presented by

the S.C. Johnson Company (Johnson Wax) called "To be alive!"

The film celebrated the joy of life found worldwide and in all

cultures. The movie went on to win an Academy Award in 1966.

The Fair is remembered

as the vehicle Walt Disney used to design and perfect the system

of "audio-animatronics" where a combination of sound

and computers control the movement of life-like robots to act

out scenes. Disney was responsible for the creation of four shows

at the Fair. In the "It's a Small World" attraction

at the Pepsi-Cola pavilion, animated dolls and animals frolicked

in a spirit of international unity on a boat-ride around the

world. General Electric sponsored "Carousel of Progress"

where an audience seated in a revolving auditorium saw an audio-animatronics

presentation of the progress of electricity in the home. Ford

Motor Company presented Disney's "The Magic Skyway"

featuring life-sized audio-animatronic dinosaurs and cavemen.

And at the Illinois pavilion, a life-like Abraham Lincoln recited

his famous speeches in "Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln."

Disney relocated many of these these exhibits to Disneyland following

the Fair (and subsequently to other Disney Theme Parks) where

they continued to delight audiences for years.

Federal

and States Exhibits

The Federal Government's

exhibit was titled "Challenge to Greatness" and focused

on President Johnson's "Great Society" proposals. The

main show in the multi-million dollar pavilion was a 15-minute

ride through a filmed presentation of American history. Visitors

seated in moving grandstands rode past movie screens that slid

in, out and over the path of the traveling audience. Elsewhere,

tribute was paid to recently assassinated president John F. Kennedy

who had broken ground for the pavilion back in December, 1962.

New York state

played host to the Fair at it's six-million dollar open-air pavilion

called the "Tent of Tomorrow." Designed by famed modernist

architect Philip Johnson, the pavilion also boasted the Fair's

high spot observation towers.

Wisconsin exhibited

the "World's Largest Cheese." Florida brought a Porpoise

show and Water Skiers to New York. Oklahoma gave weary Fairgoers

a restful park to relax in. Missouri displayed their state's

space related industries. At the New York City pavilion, a huge

scale model of the City of New York was on display complete with

a simulated helicopter ride for easy viewing. Visitors could

dine at Hawaii's "Five Volcanoes" restaurant.

Controversial

Ending

The Fair came

to a close embroiled in controversy over allegations of financial

mismanagement. Controversy had plagued it during much of its

two-year run mainly due to Robert Moses' inability to get along

with the press. As a result the press seemed unduly harsh on

the Fair, criticizing everything from a perceived lack of fine

arts displays to the price of admission to charges that the Fair

smacked of crass commercialism. It was no secret that the attendance

had been disappointing. Only 24 million people attended the Fair

by the close of the 1964 season. Whether the attitude of the

press played a part in poor attendance or whether the apathy

of New Yorkers toward the Fair gave the press an additional excuse

to attack it is open to debate. But it was a gross accounting

error brought to light at the close of the 1964 season that gave

the press their most destructive ammunition.

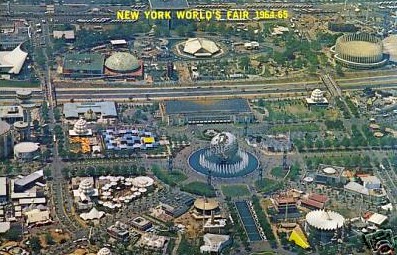

The Fair looking east over

the Amusement Area

|

The Fair Corporation

had taken in millions of dollars in advance ticket sales for

both the 1964 and 1965 season. The receipts of these sales were

booked entirely against the first season of the Fair. This made

it appear that the Fair had plenty of operating cash up to and

including the first season when, in fact, they were inadvertently

borrowing from the second season's gate to pay the bills. Before

and during the 1964 season, the Fair spent lavishly despite attendance

that was considerably below expectations, simply because there

was so much money in the coffers. By the end of the 1964 season

Moses, and the press, began to realize that there would not be

enough money to pay the bills and the Fair teetered on bankruptcy.

There would be millions of people attending in 1965 who had tickets

to enter but whose receipts had already been spent. The press,

and soon the city of New York, began to demand accountability

for what they considered gross mismanagement of the Fair.

The Fair was

eventually able to limp through the second season without having

to declare bankruptcy because of emergency monies provided by

the city, an increase in ticket prices and a surge in attendance

as the Fair drew to a close. However, the financial crisis further

tarnished the image of the Fair and of Robert Moses who was seen

to be taking personal advantage of the Fair after the escrow

account guaranteeing his one million dollar salary was discovered

and made known to the public by the New York press.

Epilogue

Like its predecessor,

the 1964/1965 New York World's Fair lost money. It was unable

to repay its financial backers their investment and it became

embroiled in legal disputes with its creditors until 1970, when

the books were finally closed. Most of the Fair was completely

demolished within six months following the Fair's close. Only

a handful of pavilions survived, some of them traveling great

distances following the Fair: The Austria pavilion became a ski

lodge in western New York; the Wisconsin pavilion a radio station

in Neillsville, Wisconsin; the US Royal Tire-shaped Ferris Wheel

a road sign along a Detroit, Michigan Interstate highway; the

Pavilion of Spain relocated to St. Louis and now a part of a

hotel; the Parker Pen pavilion became offices for the Lodge

of Four Seasons in Lake-of-the-Ozarks, Missouri, the Johnson

Wax disc-shaped theater was reworked and became a part of the S.C. Johnson

office complex in Racine, Wisconsin; the Christian Science pavilion

a church in Poway, California.

New York City

was left with a much improved Flushing Meadows Park following

the Fair, taking possession of the Park from the Fair Corporation

in June, 1967. At the center of the park stands the symbol of

"Man's Achievements on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding

Universe" - the Fair's Unisphere symbol, depicting our earth

of The Space Age. The city also received a multi-million dollar

Science Museum and Space Park exhibiting the rockets and vehicles

used in America's early space exploration projects. Both the

New York state pavilion and the Federal pavilion were retained

for future use. No reuse was ever found for the Federal pavilion

and it was demolished in 1977. The New York state pavilion also

found no residual use and continues to deteriorate in the Park.

The Space Park deteriorated due to neglect and was eventually

removed from the Park. The Fair's Heliport has found reuse as

a banquet/catering facility called "Terrace on the Park."

In the late 1970s,

Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, as it is now called, became the

home of the US Tennis Association and the US Open tennis tournament

is played there annually. The former New York City building is

home to the Queens Museum of Art and continues to display the

multi-million dollar of the model of the city of New York.

The Fair is a

distant memory for most who were visitors. Those who were children

at the time of the Fair are in retirement today. After years

of neglect, the Fair's legacy structures at Flushing Meadows-Corona

Park are being refurbished. New York, in recent years, has begun

to realize how important that Fair was to our country's and their

city's history and how much it represented an era to millions

of Americans. It was a time when the possibilities of the future

looked so bright and its possibilities seemed to be just around

the corner.

Author's note:

This essay was originally written by this author for www.wikipedia.org.

|