|

Everyone wanted to "Come to the Fair!"

After all, it was going to be the New York World's Fair.

New York was the center of the universe in the mid-twentieth

century. Headquarters to the United Nations, it was the world's

capitol. Headquarters to the largest financial institutions and

corporations, it was the economic center of the universe. A twelve-story

globe in the middle of the Fairgrounds was no small boast. To

be a part of New York's World's Fair was an expression

of power and prestige. And the opportunity to sell a message,

a product or a nation to 70 million projected visitors was a

tantalizing prospect indeed.

The press reported with great fanfare the

announcements of the Fair Corporation. Week after week new countries,

states, companies and organizations were signing on with the

Fair. Steadily, the huge site map at the Administration Building

began to fill with the names of exhibitors who had agreed to

lease space. By the autumn of 1962, the map boasted such names

as General Motors, the Soviet Union, Puerto Rico and the Virgin

Islands, Argentina, Mexico, Kodak, The World of Food, The World

of Toys, the Heartland States, Japan, Ecuador and the State of

Georgia, to name just a few.

Exhibiting at the Fair would be an expensive

proposition. Site rental and import duties on construction materials

and exhibits had to be considered. Architectural and engineering

fees, landscaping costs, and union labor to construct pavilions

were another consideration. Then there were the costs of operation

once the Fair opened: staffing and grounds upkeep and refuse

removal. These weren't Topeka costs. These were New

York costs.

The Bureau of International Exhibitions

(BIE) had denied official approval of the Fair and the thirty

(mostly western European nation) members of the organization

were banned from officially participating. The Fair Corporation

was forced to solicit trade and commerce organizations within

these countries to host exhibits in lieu of official government

participation. If Switzerland was barred from displaying her

national culture because of membership in the BIE, perhaps the

Swiss watch industry could be persuaded to exhibit their goods

to represent Switzerland in her place. Or perhaps not. The stronger

the trade or commercial industry, the more likely the participation

of the international state. Nations who were not a party to the

BIE were often poor or just emerging from years of colonial rule

and found it difficult to secure funding for representation at

the Fair despite eagerness to show their pride in new-found nationhood.

And while New York's unofficial World's Fair was trawling

the world for participation, official BIE sanctioned World's

Fairs in Seattle (1962) and Montreal (1967) were vying for a

piece of international budgets as well.

In the case of the American states, legislative

approval had to be gained and appropriations made from tax revenue

to host a pavilion. Some legislatures met for only a few months

out of the year and lacked time to enact legislation. Many had

to budget for participation and sell the idea of being a part

of the Fair to constituents. If official state government sponsorship

couldn't be gained, perhaps a trade or commerce organization

within the state would sponsor a state's pavilion. Or perhaps

not.

The 1939 World's Fair had constructed "halls"

where multiple industrial firms could rent exhibit space at a

nominal fee from the Fair. Many of these Fair-sponsored pavilions

had gone half-empty and were money losers for the first New York

World's Fair. This World's Fair vowed not to make the same mistake.

Smaller companies who wished to participate would have to sign

on with private organizations looking to put up such structures

as "The Transportation & Travel" pavilion and the

"Marine Center." However, these structures could only

be constructed if enough clients could be found to make the enterprise

profitable for the sponsor.

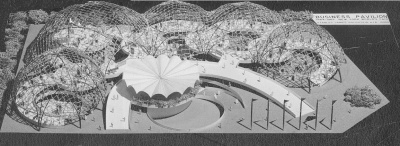

Small

Business Pavilion

|

|

| A proposed multi-exhibitor, the

Small Business Pavilion would have consisted of five connected

geodesic domes housing exhibits of smaller American businesses

in a mall-like atmosphere. The pavilion was never constructed. |

In the final analysis, the high costs,

the BIE fiasco and the aversion of the Fair to provide little

if any financial support to any exhibitor made it virtually impossible

for many eager participants to come to the Fair. Exhibiting at

the New York World's Fair was the dream of many. In reality,

it was simply too expensive for all but a few. It is no wonder

then that the map of the Fair began to fill with "phantom"

pavilions as this reality sunk in. Major exhibits, announced

with great flourish, would quietly disappear from the site map

with little or no comment. The Fair was not as anxious to share

their disappointments with the public as they were their successes.

Thus, the pavilions of Russia, France, Israel, the Netherlands

and Italy; the Graphic Arts pavilion and The World of Toys; the

Michigan, Georgia and Alabama pavilions; the Grayson-Robinson

Stores and Aero Space pavilions, along with many others, simply

disappeared leaving behind only a press clipping, a name on a

map or a few architectural renderings.

|