|

Easily the Better Living

Center's signature exhibit of "high culture," this

third floor exhibition featured forty-one paintings and five

works of sculpture by some of America's most famous artists from

the 17th century to the present. Sponsored by Maine's Skowhegan

School of Painting and Sculpture it represented an attempt, as

the exhibit's guidebook noted, to show how "the aspects

of a changing America are recorded by artists whose accents and

manners vary, but whose vision of the truth is steady."

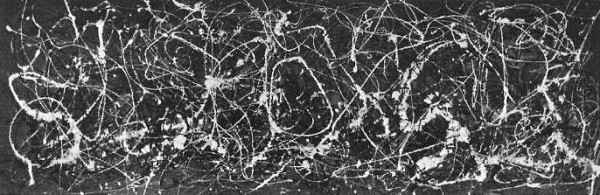

This unifying structure, the exhibitors argued, could be seen

in works as diverse as an 18th century Gilbert Stuart portrait

and a 20th century Jackson Pollock "action painting."

The exhibition was one

of the few art exhibits and displays at the Fair to earn praise

from the New York Times' art critic, John Canaday. He described

"Four Centuries of American Masterpieces" as "closer

to being a summary than you would think so small a show could

be," and that the works had been "selected with such

discernment that this minor exhibition becomes a major pleasure."

Canaday's lone complaint? The fact that in order to see the exhibition,

one had to follow the proscribed path of seeing the "entire"

Better Living Center. But even if the route hadn't been forced

upon visitors, it still offended Canaday's sense of esthetics

to see such an exhibit in close proximity to displays from Hershey

Chocolate, Borden, Sunshine Biscuits and a nine-hole miniature

golf course. "They are worth seeing, but to get there, and

out again, without suffering spiritual and esthetic offense on

the way, is impossible." Because of the Fair's general surroundings,

Canaday was of the opinion that art exhibitions in general, even

good ones like "Four Centuries," amounted to a waste

of time because the proper way to appreciate good art would not

be there.

Perhaps it was out of the

ordinary to see such an impressive display of American art in

close proximity to a musical revue show about a cow. But in the

end, that only served to demonstrate the very nature of what

the Better Living Center was all about. A pavilion that represented

diversity in its truest sense.

|

History in Portraits

|

Gilbert Stuart tartly maintained that "no one would paint

history who could do a portrait," but as the chief depicter

of George Washington, he showed that to paint portraits is often

to paint great history. Over the centuries, on a less exalted

plane, an amazing amount of homely personal history also stuck

to the brushes of the portrait painters, but the daguerreotype

and the photograph in the end reduced this broad popular stream

of American art to a trickle. The rise and decline of portraiture

is the most striking theme of a World's Fair exhibit called "Four

Centuries of American Masterpieces" and housed in the Better

Living Center.

More Doll Than Boy. The first New World painters called themselves

artisans and drew picture signs for taverns, or coated fire buckets,

depending on the state of business. In that stern and frugal

age, a commission for a portrait was a plum. "Limning"

a portrait meant producing a flat two-dimensional likeness, and

what what gives tang to these works now is the period flavor

and not any sureness of craft or conviction of life. Primitive,

untutored and serene, the anonymous 1670 Portrait of Henry Gibbs

is a charming example of the limner's style.

|

Portrait Of Henry Gibbs (1670)

|

|

The floor is in perspective; little Henry is not. More girl

than boy, more doll than either, the child seems to be floating

through the picture, not rooted in it. Yet the boy's and the

painting's mood of grave, graceful self-possession is undiminished

after nearly three centuries. In time, the limners became the

itinerant painters who criss-crossed the continent by foot, horseback

and wagon well into the 19th century, painting family portraits

in return for food and temporary lodging.

Artists of loftier vocation expatriated themselves to study

in England and to absorb the classic mastery of Renaissance portraiture.

John Singleton Copley was one such, but before he left U.S. shores,

he had already put together a masterly portrait gallery of some

of his fellow Bostonians. His Portrait of Nathaniel Hard, a famed

silversmith and engraver, stares back at the observer with a

keen, curious, probing intensity that is uncannily lifelike.

As John Adams said of Copley's portraits: "You can scarcely

help discoursing with them, asking questions and receiving answers."

|

Portrait Of Nathaniel Hard (c. 1765-1770)

|

|

Bravado & Bravery. The idea that portraits were history came

naturally to Western Painter George Catlin. In the 1830s he resolved

to assemble a pictorial record of the last golden years of the

Indians freely living their own lives. He rode across hundreds

of miles of unmapped prairie, visited 48 tribes and painted 600

pictures. His Indian Boy is a triumph of photographic realism

blended with psychological insight. There is a trace of bravado

in the boy's stance, backed by ultimate bravery in the clenched

right fist. Around the eyes and mouth is the faint hint of sadness

of a boy fated never to roam and rule the land of his father. |

Indian Boy (1835)

|

|

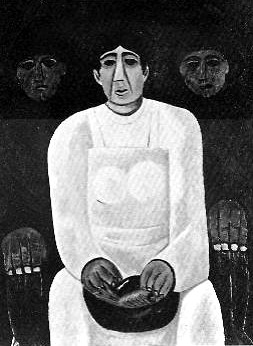

The mask of anguish in Marsden Hartley's The Lost Felice hides

a different sort of grief. It is a symbol of womanhood mourning

her drowned sons. The 20th century's passion for abstraction

makes any representational figure seem accessibly human, but

the grieving mother in Hartley's picture resembles a woman only

in the way that an eerie echo resembles a voice. The intentional

distortions of the 1939 picture ironically complete the cycle

begun with the unintentional distortions of the 1670 picture.

Perhaps fittingly, the decline of portraiture ends without a

portrait |

Lost Felice (1939)

|

-

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956)

-

-

Arabesque, 1948

-

Oil on canvas, 37 x 117

-

Coll. Richard Brown Baker

|

SOURCE: Souvenir

Guidebook, Four Centuries of American Masterpieces |