|

An historic Civil War locomotive!

... The world's largest model train exhibit! ... Daily shows

featuring the latest fashions from America's leading designers!

... A dream house display of home furnishings! ... Exotic animals

living naturally among home furnishings! ... A flowing water

faucet seemingly suspended in mid-air! ... Priceless works of

American art! ... Tasty samples of chocolate and cookies! ...

A musical revue puppet show featuring one of the most famous

commercial symbols of American industry!

Does that sound like the

kind of diversity that best epitomizes the things to be found

in the vast 600 acres and 150 plus pavilions of the 1964-1965

New York World's Fair? Actually, all of this could be found in

one building alone: The Better Living Center, situated in the

Industrial Area and flanked on either side by two of Walt Disney's

major attractions, the General Electric and Pepsi Cola pavilions.

This four story structure was both the tallest and largest in

the entire Industrial Area and was meant to provide, not just

a diversity of exhibits, but an outlet for exhibitors who wanted

to be involved with the Fair yet were unable or unwilling to

spend the money necessary to build their own pavilion. In addition,

those exhibitors who might have at first glance been more at

home in a more specialized building like the Pavilion of American

Interiors or the (never-constructed) World Of Food conceivably

saw the Better Living Center, with it's "potpourri"

approach of a variety of exhibits dedicated to the theme of better

living, as an ideal place to call attention to themselves in

a smaller setting.

-

Ground

Level view of the Better Living Center

SOURCE: New

York World's Fair Publicity Photograph presented courtesy Craig

Bavaro collection

|

|

The 1964-1965 New York

World's Fair's own "potpourri" approach of soliciting

sponsors for multi-exhibitor pavilions, whether done consciously

or not, hearkened back to the first significant World's Fair

in London in 1851. For that Fair all of the industrial exhibits,

scientific demonstrations and international displays were housed

inside one facility, the massive glass and iron "Crystal

Palace. " The success of the "Great Exhibition"

of 1851 insured that the legacy of the Crystal Palace would never

be forgotten. The Better Living Center, World of Food, Pavilion

of American Interiors, Hall of Education and the Transportation

& Travel Pavilion were all privately sponsored, multi-exhibitor

buildings and among the largest structures at the at the 1964-1965

Fair. By their nature they were the Fair's own Crystal Palaces

-- yet not constructed or financially supported by the Fair itself.

Interestingly, a history-minded organizer of the Better Living

Center was no doubt thinking back to 1851 when it was decided

that one of the major exhibits planned for the building, a daily

fashion show, would be called "The Crystal Palace of Fashion."

Promotional advertising

for the Better Living Center suggested that it might be a pavilion

geared more toward women. That certainly seemed true with such

planned exhibits as The Crystal Palace of Fashion and the presence

of a "Women's Hospitality Center." But there were plenty

of other exhibits that cut across gender lines, as well as others

that were aimed at children. With an observation deck offering

one of the best views of the entire Fair next to that of the

New York State Pavilion's observation towers, and a rooftop

restaurant, the Better Living Center should surely have been

able to draw in large crowds of Fairgoers of all ages. Such

was not to be the case. While the Better Living Center ultimately

didn't do as poorly to the degree that true disasters like the

Pavilion of American Interiors or the Hall Of Education did,

it was one of the Fair's more conspicuous failures. Even its

prime location next to some of the Fair's biggest successes did

not help it.

The Better Living Center

had to overcome a rocky beginning. It failed to open smoothly

in April, 1964 with the rest of the Fair. A number of top exhibits,

especially those on the third floor, were not ready on Opening

Day and weren't fully in place for as much as a full month after.

As Better Living Center President Richard Burge explained in

a May 26, 1964 letter to Fair officials discussing the state

of the pavilion, "There are very great problems inherent

in effectively coordinating and installing in excess of 125 exhibitors

in a building of the nature and size of ours." Construction

delays in getting new exhibit space finished after the Fair opened

grew so bad that the pavilion operated during its first month

without a formal Operating permit (third floor exhibitor Canada

Dry regarded the building conditions as "deplorable").

This led the Fair's Director of Safety, W.J. Hyland, to make

a subtle threat that unless problems were immediately dealt with

he might have the pavilion closed. Burge then employed work crews

around-the-clock to make sure Hyland's objections were addressed.

The major problem with

the Better Living Center was that it forced Fairgoers to take

only one proscribed route through the pavilion to visit the exhibits.

All visitors were required to start their tour from the

top floor by taking the Lifesavers-sponsored glass elevator to

the rooftop restaurant or an escalator that went from the Lobby

to the first floor mezzanine, then a second escalator leading

to the third floor exhibit area where they would begin to wind

their way down through every exhibit in the building.

The New York World-Telegram, in what was for the most

part a favorable profile of the pavilion, likened the whole design

to that of a mousetrap aimed at trapping Fairgoers into seeing

every part of the building (and forcing them to follow yellow-painted

footprints on the floor as they made their way down). For someone

who was only interested in seeing one or two specific things

in the pavilion, there might have been a disinclination to enter

the building and allow oneself to be "trapped" for

however long it might take to make one's way back down -- having

to enjoy (or endure) every exhibit along the way. By designing

the building this way the pavilion's sponsor, Edward H. Burdick

Associates., Inc., could assure exhibitors that they would get

their money's worth out of exhibiting in the Better Living Center.

Once inside, the Fairgoer had no choice but to

see their exhibit. It was a classic example of an "idea

that looked good on paper." Ultimately, this concept kept

more people away than it enticed to venture in.

Despite its ultimate failure

the Better Living Center's mere existence, and a closer look

at some of what it had to offer, can provide a genuine insight

into the nature of what Robert Moses called "Something for

Everyone" and the vast scope of what the 1964-1965 New York

World's Fair was all about.

So ... taking the proscribed

route of top floor down, let's visit the Better Living

Center!

-

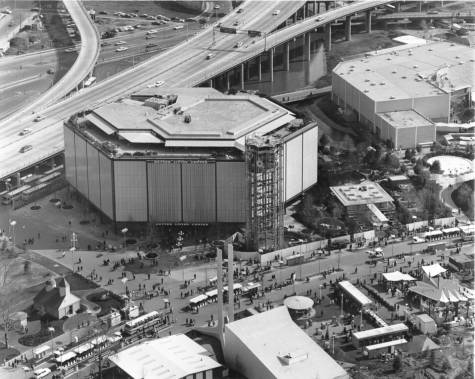

Aerial

view of the Better Living Center

-

(View a Larger Version of this Photograph)

SOURCE: New

York World's Fair Publicity Photograph presented courtesy Craig

Bavaro collection

|

* * *

|