|

One of the things that

Robert Moses and his associates had learned early in their careers

was that if you wanted to build something really big one important

way to garner support for the project, as well as to assist the

builders during the planning stages, was to commission a very

detailed model. Never was this truer than for the models that

they had built to both illustrate and publicize the New York

World's Fair of 1964-1965. And according to Moses, the self avowed

model man per his own notes in the Fair records, there was no

better way to attract exhibitors to the Fair and build excitement

with the public than to have a large and dramatic visual representation

of what great and exciting things were coming to the Fair.

A Big Model for a Big

Fair

The model which ultimately

came to be referred to as simply "the big model" became

the responsibility of Deputy Director of States Exhibits Mike

Pender on January 3, 1961 by a memo issued by Robert Moses. But

the story of the model began much earlier than that with the

original proposal that Lester Associates, Inc. made to the Fair

Corporation on August 3, 1960 in which they state that the basic

model map (not including any buildings) would cost $40,500 to

build. As soon as the Fair took possession of the model, the

almost constant updating of it to reflect the changing landscape

began immediately. As new exhibitors signed their leases the

selected plots were marked on the big map to indicate where they

would be located. The map itself was color coded similar to the

later official published maps of the grounds to indicate the

five different exhibit areas of the Fair along with roads being

marked in brown and park areas in green.

From early 1961 until early

1964 Mike Pender was charged with the task of communicating with

Lester Associates to obtain bids for the building and installation

of the various structures in miniature. As plans were announced

Mr. Pender would then work with the engineering and publicity

departments of the Fair to obtain the drawings, sketches, specifications

and artist renderings of the buildings to provide to Lester to

bid the work, and for Lester's artists to ultimately use in constructing

the accurate representations of the structures. Once Lester received

this information they would provide a bid to the Fair which would

be reviewed and approved by Mike Pender prior to work commencing

under a standing contract that they had with the Fair. At regular

intervals time would be reserved for Lester's people to have

exclusive access to the model room to install the new or updated

structures on the big model. The flow of information back and

forth between the Fair and Lester was continuous as new leases

were signed, exhibitors' building plans announced, revised or

ultimately scaled back and even sometimes dropped from the Fair.

Once a lease was signed usually a small plaque would be placed

on the corresponding lot on the model. Then as exhibitors formalized

their building plans those details would be provided to Lester

to build a scale model of the pavilion in miniature. The typical

cost of rendering each of the pavilions usually cost less than

one hundred dollars for the smaller ones such as SKF or Morocco.

The slightly larger pavilions such as Illinois or New Mexico

typically cost one to two hundred dollars. The really large exhibits

such as IBM or GE would routinely cost between three and five

hundred dollars each to build. One unusually complex model was

the Chrysler pavilion which ended up costing the Fair the sum

of $921 initially plus another $215 for changes when they ultimately

finalized their pavilion designs. Installation was extra and

billed based on the actual hours spent on the big model doing

the work.

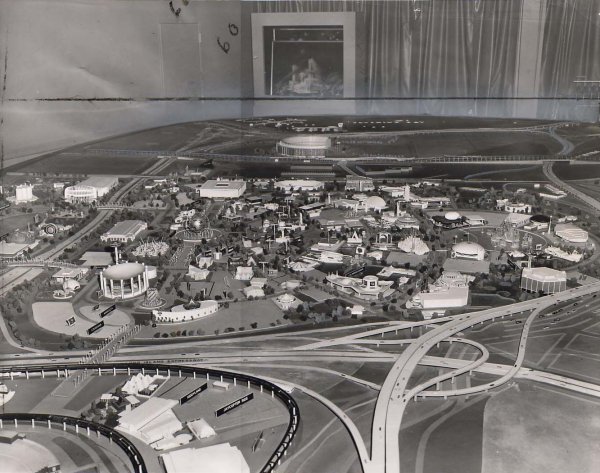

The model as it appeared on display

in the Administration Building

|

An example of the great

attention to detail was whether to build an animated or stationary

version of the Monorail. Lester estimated that to build an animated

version would cost $800 whereas a stationary version would only

cost $350. After some discussion back and forth as to the importance

of this exhibit it was ultimately decided that the animated version

would be built and so it was ordered. One has to keep in mind

that all of these amounts are in early 1960s dollars so they

were no small sums even back then. Another interesting story

that illustrates how seriously the Fair and ultimately the exhibitors

viewed the importance of the big model and its timely, as well

as accurate, representation of their plans is reflected in the

communication back and forth between the CEO of the Parker Pen

Company and the Fair. After a visit to the model room the CEO

was quick to dash off a letter to Fair officials demanding that

they immediately update the model. He most emphatically stated

that he felt that they had already had an adequate amount of

time since Parker's participation announcement to update the

model with their exhibit building as well as the narration that

the hostess provided to visitors. Of course the Fair responded

quickly that they too felt this was of the utmost importance

and expected that within no more than eight weeks, or sooner

if possible, the necessary changes would be made.

Lost but Not Forgotten

The big model was also

the only place that some of the unbuilt pavilions at the Fair

would ever be seen. This included the infamous World of Food

pavilion at the main entrance to the Fair, the American Indian

pavilion and the Graphics Arts pavilion to name but a few. One

of the most notable and well documented ideas which never came

to fruition was the Arch of the Americas. It appears that as

early as April 2, 1963, Owens Corning, which was involved with

Marinas of the Future in building the World's Fair Marina, was

very interested in acquiring their own full scale version of

the big model to display in their showroom in midtown Manhattan.

They were duly referred to Lester who quoted them the tidy sum

of $60,000 to build a basic flat model which included only sixty-three

of the pavilions designed and built to date! If they wanted the

model with the same contours as the actual Fair site the cost

would increase by another $7,500; with sound, another $5,000

on top of that. There is no indication that this version was

ever built. But what did come out of this discussion was their

interest to be involved with the Fair on the same level as that

of US Steel. To that end they proposed building an arch entirely

out of fiberglass and for them to receive, in return, a considerable

amount of publicity at Fair expense for sponsoring the construction.

For a short period of time this idea intrigued officials including

Moses who went as far as to direct Mike Pender to have a miniature

model of the arch designed and built for the big model to see

how it would look. While it does appear that the model arch was

built and actually placed on the model its display there was

short lived. This was due in large part to the Fair's unwillingness

to provide the requested level of publicity for the arch for

Owens Corning as they did for US Steel. So the arch came off

the model as quickly as it went on.

SOURCE: World's

Fair Progress Report #8, April 22, 1963

|

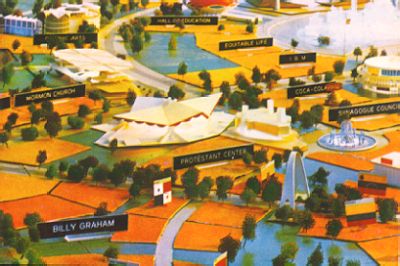

The model was truly a

"working model" and was changed all the time. Black

placards with the name of the pavilion, along with a cut-out

"footprint" of its plot, represented the exhibitor

until a model could be constructed. Site cut-outs were color-coordinated

by "area" of the Fair (you can tell the orange International

Area plots from the gold Industrial Area plots at-a-glance, etc.)

This photo is a good example of how the model changed. The archway

in the lower center of the picture is "The Arch of the Americas"

that was never constructed. The model was removed when plans

were dropped. Likewise, the building in the center of the photo

with the cantilevered four-point roof is called The World's Fair

Assembly Building. It became known as the World's Fair Pavilion

and took the shape of a geodesic dome. The dome would replace

the four-point building in later photos of the model.

|

Let There be Light!

When the model was originally

built the structures were not lit from within. As time progressed

Moses decided that the big model needed a very elaborate lighting

system to highlight each structure individually or in groups

corresponding to the five sections of the Fair. At the same time

parts of the model were also painted using phosphorescent paints

to simulate what the Fair would look like at night. This elaborate

retrofit alone cost in excess of $5,000 to complete and included

the addition of black lights in the ceiling above the model to

simulate a night view. As more and more buildings were completed

the lighting system had to be upgraded to meet the power demands

for all of these lights. This was accomplished by adding more

powerful transformers under the model. The lighting effects were

controlled from what can best be described as a complex switchboard

mounted on one side of the model which the operator could switch

on and off in various combinations to produce the desired effects.

All of this lighting caused an unforeseen problem in the close

quarters of the model room. An incredible amount of heat would

build up under the model if left fully on for long periods of

time. This became quite apparent one day when a small wisp of

smoke was noticed coming out from the underside of the model!

Alarmed, Fair officials promptly summoned Lester down to the

Fair site to determine what was causing this very worrisome problem.

Their inspection of the underside of the model revealed that

poor ventilation was allowing the steady build up of heat from

the continuous operation of the lights. This excessive amount

of heat was overloading the circuits and thus causing them to

smolder. Lester promptly recommended that more vents and some

small fans be added at various points along the skirt lining

the model to improve air circulation and that a timer be added

to the light board so that after a certain period of time the

lights would automatically shut off if left unattended. Most

importantly they chastised the Fair for storing various items

underneath the model which they felt was a serious fire hazard.

The Fair Corporation swiftly agreed to these recommendations.

Thus the model was saved from its own imminent and what would

have been a most untimely demise.

Presenting Unisphere (please

stand back though)

On March 24, 1961, General

Potter indicated that Moses had approved the spending of $8,000

to build a 3'9" replica of Unisphere by an unknown firm

on the west coast of the United States. This model ultimately

had its own separate display area in the Administration Building

surrounded by a curtain backdrop and a railing to keep visitors

from getting too close to it. Access to this room was very tightly

controlled with strict instructions to the World's Fair Maintenance

personnel that they could clean everything around and attached

to the model but that under no circumstances were they ever to

actually touch the model for any reason. The records do detail

though how it was once moved to be photographed and filmed by

US Steel for publicity purposes prior to the opening of the Fair.

The memo goes on at length as to what care was to be used in

its handling during the move back and forth from a conference

room where the shoot was to occur. Also of interest is the mention

of how a study was done using this same model to determine that

to have lighted and moving satellites on the three orbit rings

of the real Unisphere would cost anywhere from $100,000 to $150,000

to design and implement and that such a cost would not be practical.

This very novel idea died a quiet death. Just as interesting

though, the records do not detail whatever happened to this very

elaborate and expensive model of the Unisphere after the Fair.

Almost Done, Now What?

What is also interesting

to note about the big model is that while it was not actually

finished until early March 1964 it was at the same time in great

peril of being put in storage or worse yet destroyed unless another

suitable location could be found to display it in. This was because

as the Fair administration staff grew in size so did their need

for suitable and conveniently located office space. The biggest

group in need seemed to be the accounting staff which was growing

exponentially along with the Fair. Since the accountants obviously

were not model men one of the first places they decided to look

to take over was the model room. And so through a good part of

1963, while work still continued on the model, one group of Fair

officials was plotting and scheming against the model while another

group was feverishly working on a plan to find a suitable permanent

home for what was now a very elaborate and very expensive rendering

of the Fair.

Early during this process

it was proposed that a small sponsored pavilion be built at the

main entrance to the Fair and that the model would be lent to

that sponsor free of charge to display in this unique building.

The model would serve as the focal point of the exhibit to help

orientate visitors as they entered the Fair. Fair officials went

as far as to commission a structure designed by no less than

Edward Durell Stone that can best be described as a very graceful

ribbed wing-like permanent structure that was to be set below

grade. A picture of the rendering of this proposed structure

exists in the records and was obviously shown to prospective

sponsors to entice them to participate in the Fair. Fair officials

estimated that such a building would cost anywhere from two to

three hundred thousand dollars to build not including outfitting

the sponsors own exhibit space and staffing it. They also indicated

to all prospective exhibitors that while use of the model would

be offered most generously free of charge, the moving of it would

not be free and as such anyone interested in this idea would

have to bear the entire cost of moving the model out of the Administration

Building and into its new location. William Berns, who was in

charge of publicity for the Fair, made this one of his pet projects

to bring to fruition and Moses gave him until July 1, 1963 to

get it done. During that time the lead contender to sponsor the

pavilion was CBS. A constant stream of unsuccessful correspondence,

which included invites out to the Fair site, was directed personally

to William Paley who ran CBS. At the same time at least a half

a dozen other companies, including Eveready Battery and Wonder

Bread, were contacted as possible sponsors all with no success.

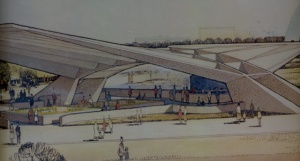

Proposed pavilion designed by

Edward Durell Stone that would display the model of the Fair.

No sponsor was found and the structure was never built.

SOURCE: unknown,

contribuion of Gary Holmes

|

RCA was also approached

to add the model to their pavilion but they quickly indicated

that at this late stage it was not possible to modify their pavilion

to accommodate it. Things were actually starting to look desperate

as extension after extension was granted until, at almost the

last minute, Mike Pender somehow convinced American Express to

take the model. In a handwritten note at the bottom of one memo

Bill Berns marveled at how Mike pulled it off and promised to

take him for a steak dinner in the restaurant of his choice for

saving the day! And so a deal was struck with Amex for delivery

of the model to occur no later than March 1, 1964. But the model

was not out of the woods yet since even at this late stage it

was far from complete. In the waning days of 1963 and early 1964

there was a flurry of activity between Mike Pender and Lester

Associates as they worked closely together to get the last of

the buildings completed and installed on the model in preparation

for its delivery to American Express in its final form. Then

to add insult to injury, once the model was completed, it was

discovered that a small portion of the original outlying land

areas around the Fair had to be removed and put into off-site

storage by the Fair Corporation never to be heard from again.

This was due to the space limitations for the model at the Amex

pavilion.

SOURCE: Going

Places, May - June 1964

|

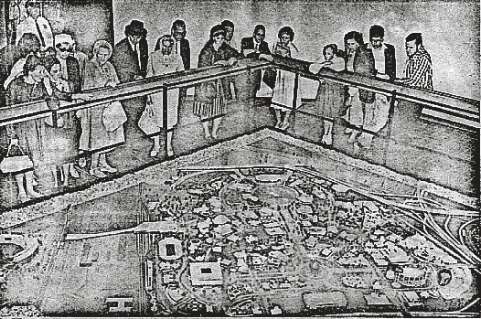

The model as it appeared

on display in the American Express Pavilion

|

What the Fair's records

don't indicate is what ultimately happened to the big model after

the Fair. While there were a few pieces of correspondence mentioning

various ideas to move the model back to the Administration Building,

the New York City building, the Hall of Science and even the

Press Building after the closing of the Fair, there is no real

solid evidence documenting that any of these ideas were actually

carried out.

He Who Signs the Checks

Gets the Freebies

Another side note to the

big model was that Robert Moses, Stuart Constable and General

Potter all received mounted versions of various unnamed pavilion

models as gifts from Lester for their desks and offices. At the

same time, on March 23, 1964, Moses directed that plaster models

also be built in 1" to 100' scale and mounted on walnut

bases with engraved nameplates. A total of twenty-five of these

types of models were ordered. The models which came in white

gift boxes were ordered for each of the eighteen state pavilions

at the Fair in addition to six of the New England States model

because it was a multi-exhibitor pavilion, and one of the US

Pavilion, with the idea of presenting them to officials as a

memento of their exhibits at the Fair. Lester priced these special

models at $30 each. One has to wonder whatever happened to each

of these unique models as well.

Have Model Will Travel

It was decided during the

pre-Fair period that in addition to the big model there would

also be a number of much smaller but no less detailed versions

that would be utilized to promote the Fair. To that end the Fair

initially had a grandiose plan to build anywhere from fifteen

to fifty of these smaller "traveling" versions of the

Fair model, the first of which ultimately cost the Fair Corporation

$9,850 to build according to a May 9, 1963 letter from Lester

Associates. In that same letter the Fair was given an option

to acquire six more traveling models for an additional total

cost of $38,600. After paying the cost for the first traveling

model though, plans to build more of these table top type models

stalled for unknown reasons. That was until November 19, 1964

when Lester offered to build the Fair another model for $4,948.

In anticipation of the promotional needs of the Fair for the

1965 season the Fair duly commissioned this additional version

thus giving it two traveling models for its use. During the period

between the above mentioned dates Lester also wrote a number

of letters to Fair officials trying to interest them in a program

whereby Lester would build a number of additional models and

then administer a rental program of their own design for these

other models. The bottom line of their very detailed proposal

ultimately centered on them renting these models out on a weekly

basis for the outrageous sum of $200 per week! Fair officials

thought just that and told Lester that maybe they could get $50

a week. Thus due to this disagreement on what to charge for the

rental program it never got much past Lester building four additional

models at their own cost and renting them for an undetermined

amount on a periodic basis.

Now this is where the story

gets interesting because the records do detail exactly what happened

to all six of these traveling models after the Fair ended! Fast

forward to early 1966 and we find our hero Moses trying to scrape

up every nickel he can lay his hands on to finish Flushing Meadows

Park. When low and behold the Plumbers Union comes along and

offers to buy one of the models for a small but reasonable sum.

Moses, ever the shrewd businessman, offers to sell them one of

his models for the sum of one thousand dollars. The plumbers

being even shrewder than Moses though quickly but politely decline

to take him up on his most generous offer since that is a lot

of money to pay just so some union delegate can say he has one

of the models in his office. Now more time passes and on March

8, 1966, Lester writes to the Fair Corporation and notifies them

that since they built the four models in their possession on

their dime they intend to keep one for themselves, donate one

to the Department of Parks and donate one to the Museum of the

City of New York which leaves one model to be disposed of. Knowing

that they made a boatload of money off the Fair for the big model,

the traveling models and, lest we not forget, The Panorama of

the City of New York, they ask Fair officials if they have any

preferences as to who should be the lucky recipient of their

final model before they decide for themselves. On March 16, 1966,

Moses says in a memo to Stuart Constable that he has already

decided that the Fair's two traveling models are going to the

Long Island State Park Commission and the Triborough Bridge and

Tunnel Authority. At the same time he recalls the plumber's request

and now realizing that he can satisfy their desire to obtain

a model in what can best be described as a declining market for

traveling Fair models, he generously tells his associate to instruct

Lester to send their last model to the plumbers. And so on March

21, 1966 Stuart Constable wrote to Lester Associates and advised

them that Mr. Moses would like them to give the last remaining

traveling model to the Plumbers Local Union #1 for their viewing

pleasure.

And so goes the saga of

the models both big and small of the New York World's Fair of

1964 -1965.

|